Sony Cyber-shot R1 retro review

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

Welcome back vintage camera lovers for another stroll down Memory Stick lane, with today’s episode all about the Sony Cyber-shot R1, a high-end prosumer model packing a Carl Zeiss 5x optical zoom and a large 10.3 Megapixel APSC sensor with Live View.

Launched in late 2005 at around $1000, the Cyber-shot R1 was Sony’s flagship prosumer camera, and while the name was new, it was the spiritual successor to the previous Cyber-shot F series, packing innovative tech into an unusual body, even if it dumped the twisting design of the F505 to F828.

The R1’s headline feature then – and now – remains a large sensor in a fixed-lens design, something that’s still a rarity today. Its potential – perceived or actual – means the R1 still commands fairly high prices on the used market, as much as $200-300 or pounds in working condition, although some sellers are open to offers and I managed to bag one for £90. So 19 years after it was first released, join me as I take it out for a spin around Brighton to see if it lives up to its promise. My full video review is below, but if you prefer to read the written highlights, keep scrolling!

The Cyber-shot R1 actually holds a special place in my heart as it was the first review I published on my Cameralabs website back in late 2005 – gotta love that left-justified static html layout – so I’ll also include some of my original results and samples to see how they hold-up almost two decades later!

Back in late 2005, the R1 entered an extremely competitive market for prosumer photographers with a grand to spend. During the previous decade, all-in-one bridge models were the only choice if you wanted a higher-end digital camera with decent control at this price point. But DSLRs with their larger sensors and the chance to swap lenses were becoming steadily affordable, and what cost tens of thousands in the mid to late Nineties was now also available for a thousand dollars.

In 2003, Sony’s Cyber-shot F828 faced existential threat from Canon’s EOS 300D or Digital Rebel, the first consumer DSLR costing much the same, and two years later the R1 found itself up against the EOS 350D or Rebel XT, which was already more refined than its predecessor.

The R1 also faced future competition from Sony itself which had already announced a partnership with Konica Minolta to develop its own DSLR, the first of the Alpha series, the following year in 2006. Indeed with most camera companies releasing similarly-priced DSLRs, what could the R1 do to compete? Let’s find out!

Like its earlier high-end all-in-ones, the R1 follows Sony’s tradition of striking a canny balance between unique product design and intuitive operation. It’s fair to say apart from sharing some DNA with earlier Sonys, there’s nothing else that looks like it, yet enough remains familiar to be up and running in moments.

Weighing a fraction under a kilo with battery, there’s no getting away from the R1’s heft, but once you add a kit zoom to a budget DSLR like the 350D, they’re not much different in overall size, and remember the R1’s lens has a broader zoom range with a slightly brighter aperture. Sure it’s still heavier than a budget DSLR kit, but it never feels unwieldy in your hands, and the build quality is excellent.

Interestingly, Sony abandoned the swiveling body of the previous F-series, and there’s still the temptation to try and twist your right hand away from you when you first pick up the R1. But while the R1’s grip remains fixed in position, it’s large and comfortable to hold, with a considerate dip between it and the main body for your thumb to curl round for added security. The lens barrel also rests comfortably in your left hand.

In place of the old swivel, Sony fitted the R1 with an articulated 2in 134k dot screen, but it’s not where you’d expect to find it on the rear. Instead it’s hidden in the head of the camera, angling up to face the subject, before twisting 180 degrees clockwise to face you.

While this now has the screen facing backwards to the photographer, the unique aspect is folding it back down again to face-upwards for comfortable waist-level shooting. Peering down to the top of the camera feels almost like composing with a classic medium format film camera, and a highlight of shooting with the R1. The screen articulation also lets you more easily frame at high and low angles when turned to the portrait or vertical orientation, something not possible with the swivel bodies of the earlier F-series.

If you prefer to compose at eye-level, there’s an electronic viewfinder with 235k dots, and unlike earlier models, a sensor can automatically switch between it and the screen. That said, if you’re shooting at waist-level with the screen, you’ll want to manually select it or your torso will have the camera annoyingly switching to the EVF.

As a prosumer camera, you won’t be surprised to compose electronically with a screen or EVF, but previous models employed smaller CCD sensors, with the R1 actually becoming the first camera to offer live view from a large CMOS sensor, several months ahead of the Olympus E330 and around two years ahead of Canon’s 40D.

The live view delivered not only more accurate coverage than most DSLR viewfinders, but could also be magnified for focusing assistance as well as displaying a live histogram with optional live zebra patterns. Again nothing new for a small sensor camera, but ground-breaking for one with a large CMOS sensor.

Pushing the monitor button during playback cycles between clean and information views, as well as one with RGB and brightness histograms. You can playback through the viewfinder or on-screen, but it does feel a bit odd to view them at the various screen angles and positions.

In classic Sony style, there’s no shortage of controls on the R1. On the rear there’s two dials positioned on either side of the thumb grip, with one clearly inspired by Canon’s flat rear wheels with satisfyingly clicky feedback. In Priority or Automatic modes, this wheel adjusts exposure compensation, while in manual mode it controls the aperture, and in playback the magnification.

Rather than Canon’s single large button in the middle though, Sony’s popped in a tiny clickable joystick for navigation and adjusting the focus area and position. There’s also dedicated buttons on the rear to access the metering, drive modes and self-timer. The metering offers two Multi modes or a spot option, while Drive switches between single, 3fps bursts or bracketing options. Meanwhile the 10 second self-timer is either on or off.

The main mode dial feels relatively small and hidden on the rear surface to the lower left of the viewfinder, when you’d normally expect it to be prominently located on the top surface of the camera. It offers the usual Auto, Program, Manual, Aperture and Shutter Priority modes along with four scene presets. Note playback has now been delegated to a separate button, like most DSLRs.

Shutter speeds range from 1/2000 to 30 seconds, along with a Time bulb option which opens the shutter with one push and closes it with a second, up to three minutes later. There’s no restrictions on the shutter and aperture combinations, and exposure compensation is offered from +/-2EV in third stop increments.

On the left side are buttons for flash and white balance options, with the latter offering Auto, five presets and a custom option. There’s also a rotary switch for focus, selecting auto, macro or manual, with the latter offering a magnified view for assistance and the chance to autofocus with a push of a button within. Meanwhile a dedicated button for ISO is located right next to the shutter release.

There’s a small pop-up flash above the lens and a hotshoe for mounting an external Sony flashgun, but now located atop the grip since the screen occupies where you’d normally find it. Slow-synchro and rear-curtain modes are offered, and flash compensation is available between +/-2EV.

The grip is also home to the card slots and battery compartment. Open a flap on the right grip and you’ll find slots for both Sony’s own full-length Memory Sticks as well as Type I or II Compact Flash cards including the IBM MicroDrive, with a switch to select the desired format.

The ability to use either format may have been intro’d two years earlier on the F828 but still felt radical for Sony. The R1 also supports FAT32 formatting for larger than 2GB cards, but I stuck with my 2GB Memory Stick Pro Duo card in an adapter for my tests.

Meanwhile the R1’s powered by the same NP-FM50 battery as the F707, F717 and F828 before it, and as an Info-Lithium pack you can see exactly how many minutes of charge remain on-screen. Most 20 year-old batteries refuse to accept any charge, but luckily replacement packs are readily available. I used an FM50 replacement battery from DSTE which I originally bought to power my F707.

The battery is charged in-camera by connecting the supplied AC-L15A adapter to a DC-input behind a flap on the left side; you’ll need this or an optional external unit to charge the battery. Joining the DC-input are a 3.5mm AV output for TV slideshows, a standard Mini USB-2 port, and an accessory jack.

Moving onto the lens, the R1 employs a Carl Zeiss Vario Sonnar zoom with a 35mm-equivalent range of 24-120mm and an optically fast ratio of f2.8-4.8. This starts wider and reaches comfortably longer than typical DSLR kit zooms.

Of course unlike DSLRs, the R1’s lens is permanently attached to the body. But while this lacks the flexibility of an interchangeable lens system, the R1’s optics offer a useful general-purpose range which you may find sufficient. It’s worth remembering many budget DSLR owners only ever used the kit zoom, which not only had a narrower range but a dimmer aperture.

The inability to remove the lens can also be spun as a benefit, reducing the risk of dust getting onto the sensor. If the R1’s range isn’t sufficient though, you can attach optional 1.7x tele, 0.8x wide or macro conversion lenses. These are however quite large, especially the tele adapter which doubles the length of the camera and adds almost an extra kilo in weight.

Like the F828 before it, the zoom is operated by a tactile mechanically-linked ring, allowing very precise adjustments. You can also screw-in 67mm filters, and a petal lens hood is supplied.

By eliminating the mirror and prism section of a traditional DSLR, Sony was able to implement a very short back focus where the last optical element is positioned immediately in front of the sensor. Sony claims this reduces the chromatic aberrations which plagued the earlier F828 and we’ll see in my sample images.

In terms of focusing, the R1 offers three areas, cycled by clicking the mini joystick. There’s multi area, centre, and a smaller single area which can be repositioned with the joystick like the F828. The focusing itself is fairly swift for static subjects, but fared less well for those in motion. This is an area where the phase-detect AF in the optical path of DSLRs had the edge for many years. Sadly the R1 also lacked the hologram AF system of the F707, F717 and F828 which projected a pattern to focus-on even in complete darkness. In its place was a simple orange LED which illuminated in dark conditions.

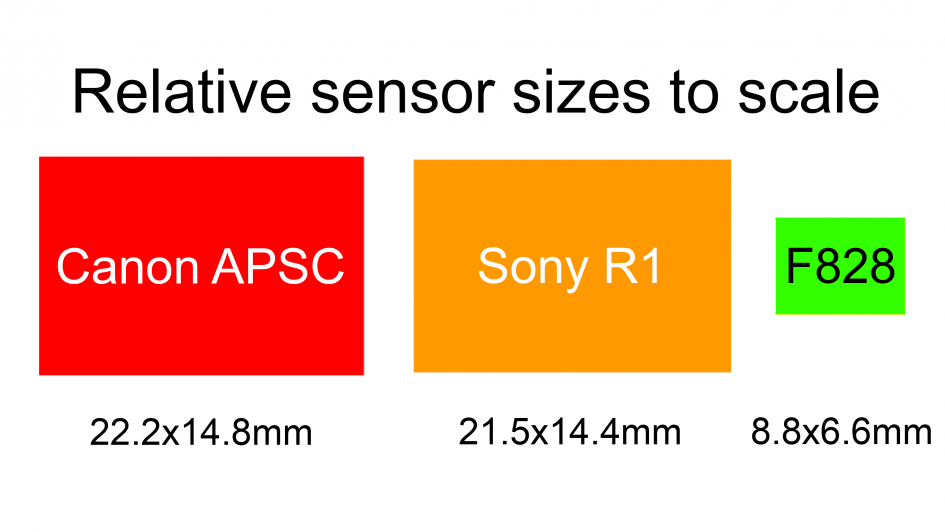

Moving onto imaging, the most unique aspect of the R1 is of course its large CMOS sensor – the first time an all-in-one camera has employed a DSLR-sized sensor. The R1’s sensor measures 21.5 x 14.4mm, so is only fractionally smaller than those found in most budget DSLRs. Crucially though it’s considerably larger than the 8.8 x 6.6mm size of the 2/3in sensor in its predecessor and other high-end all-in-ones. In fact over five times the total area, in turn promising lower noise and higher dynamic range.

The R1’s sensor has 10.3 Megapixels, recording 3:2 shaped images with 3888 x 2592 pixels. This is a step up from the six or eight megapixel resolution of the budget DSLRs around in 2005, and only matched the following year. The large sensor also allowed Sony to implement a wide sensitivity range of 160 to 3200 ISO, which while similar to DSLRs, is a significant improvement on the range of existing all-in-ones.

Images can be recorded at five different resolutions, each with the choice of two JPEG compression levels. They can alternatively be recorded in Sony’s SR2 RAW format, which additionally captures a JPEG at the same time, making it a RAW+JPEG mode. Best-quality JPEGs measure around 4.5MB each, while RAW files weigh-in at 20.5MB.

The Picture Effects menu has been reduced to just two options, sepia and black and white, although the latter is an upgrade over the F series which annoyingly excluded a monochrome option. Standard and vivid colour modes are offered, along with Adobe RGB for the first time on a Sony camera. Saturation, contrast and sharpness can also be adjusted by a notch in either direction.

While the sensor was roughly the same size as a budget DSLR, Sony was among the first to implement a CMOS design as opposed to the more established CCD. Canon may have also adopted CMOS for its early consumer DSLRs, but what made the R1 unique was becoming the first first large-sensor camera to offer Live View, something which wouldn’t come to traditional DSLRs until the Olympus E330 the following year in 2006, or the Canon EOS 40D the year after that in 2007.

In theory, Live View could also have allowed the R1 to record video, but sadly it wasn’t implemented. Maybe it was a noise, heat or power issue given the sensor was already on all the time just for composition. Perhaps it was insufficient processor or memory bandwidth. Maybe it simply wasn’t considered important at the time. Whatever the reason, it’s a shame as even with inevitable restrictions, it could have given the R1 a killer edge over rival DSLRs for several years.

As it stood though, the R1 was a photo camera only, which meant pitching an early large CMOS sensor with live view against a bunch of more established designs. Let’s see how it compares.

The R1 arrived roughly between Canon’s EOS 350D and 400D, so since I already compared it against the 350D in my original review at cameralabs.com, I thought I’d go for the 400D, or Rebel XT for this one. I’m also going to compare it against the previous F828 to see if the R1’s bigger sensor really did deliver the upgrades we hoped for.

Ok let’s start with coverage with the widest view from each camera, starting with the 400D’s kit zoom which at 29mm equivalent, should be the least wide on paper, but swapping it for the 28mm equivalent of the F828 shows them to be essentially neck in neck. Note the F828’s squarer aspect ratio of 4:3 here.

Widest of all the three though is the R1 at 24 equivalent. I’m very fond of this focal length, and it was unusual at the time to have it on a kit zoom or a camera with a built-in lens. Moving onto the long-end, the DSLR kit zoom is the weakest at 88mm equivalent. Next here’s the R1, reaching comfortably further at 120mm equivalent, but the winner here by a substantial margin is the F828 at 200mm equivalent.

The R1’s zoom range was not only broader than rival DSLR kit lenses, but optically a little brighter too, but what real-life impact does this have on portraits and close-ups?

So here I am photographed with the R1 at around 88mm equivalent to match the longest-end of the DSLR kit zoom. Now let’s take a closer look at the background blur before flanking it with similar shots from the F828 on the left and the 400D on the right. All three were using their maximum apertures at this focal length: f2.2, f4.5 and f5.6 respectively.

Here you can see the R1 in the middle is enjoying the greatest background blur, but it’s only fractionally more than the 400D’s kit zoom on the right, which in turn is only a tad ahead of the F828 on the left.

There may be visible differences here, but I’d say not enough to give the R1 a decisive selling point. I think the biggest surprise for many will be seeing how close the F828 can get thanks to its brighter aperture compensating for the smaller sensor. Meanwhile, if you were to fit the DSLR with a cheap 50mm f1.8, you’d destroy both fixed lens rivals on background blur.

What about closeup bokeh effects? Here’s the R1 focusing as close as it can to the ornament when set to its longest focal length of 120mm equivalent, where the maximum aperture became f4.8 But both the F828 and 400D’s kit zoom can focus closer. So here’s the best case from the F828 on the left, at its widest focal length where you can get within a couple of cm from the subject, and on the right the DSLR kit zoom, at its longest focal length, but again able to focus much closer to the subject.

Interestingly despite having very different lenses with different settings here, they’re actually delivering a similar magnification on the ornament, while the closer distance has enlarged those bokeh balls in the background. You may notice both Sony’s exhibit some onion-ring patterns inside their blobs, versus the DSLR kit zoom’s blobs which are cleaner inside and larger overall.

So overall I was expecting the R1 to comfortably out-perform the F828 in terms of background blur thanks to its considerably larger sensor and fairly bright lens, but in my two examples, this may not be as decisive as you’d hoped or even show any benefit at all.

Next for resolution, and here I tried to frame the same composition at around the 50mm focal length, matching their horizontal coverage as best I could. Let’s take a closer look and as a side note, the DSLR proved hardest to match as the optical viewfinder delivered the least accurate coverage, thereby requiring multiple adjustments.

With the F828 on the left, the R1 in the middle and the 400D on the right, you can see their respective detail and processing styles. Both Sony’s share a similar style, but the 8 Megapixels of the F828 are clearly being out-resolved by the pair of 10 Megapixel models to its right.

Meanwhile I’d say the R1 and 400D share a similar degree of real life detail, with the Canon on the right only looking a tad softer due to lower in-camera sharpening by default.

Now let’s move onto noise and to measure their respective performance, I photographed this bunch of flowers at each of their ISO settings. This is where the large sensor of the R1 should deliver cleaner results than the smaller-sensor of the F828, and roughly match the DSLR. Let’s take a closer look to find out.

Once again you’re looking at magnified views of the F828 on the left, the R1 in the middle and the 400D on the right, starting here at their lowest sensitivities of 64, 160 and 100 ISO respectively. Here you can see the two larger sensor cameras looking a little softer due to lower sharpening, but cleaner than the F828 on the left which exhibits a little noise even at its base sensitivity. Boosting the 828 a tad to 100 ISO increases this further.

Setting them all to 200 ISO has minimal impact on the R1 and 400D, but the F828 is showing steadily more noise. At 400 ISO, the F828 on the left continues to deteriorate, but interestingly you’ll now see some noise artefacts on the R1 in the middle compared to the 400D on the right.

At 800 ISO, all three cameras are showing signs of deterioration, with the F828 on the left suffering most of all – in fact this is it’s maximum sensitivity. Meanwhile the R1 in the middle may be cleaner than the 828, but has fallen behind the 400D on the right. The Canon may be showing some noise artefacts, but they’re not as obvious.

This difference becomes even greater when increasing the two larger sensor models to 1600 ISO, where the R1 looks considerably worse than the 400D to its right. This is the maximum sensitivity of the DSLR, but the R1 bravely offers a 3200 ISO option which is so noisy it’s really for emergency use only.

These results mirror what I found when testing the R1 back in 2005. Its larger sensor is certainly much cleaner than the small sensor models which preceded it like the F828, but it’s not a match for a rival DSLR of the same period. Maybe the sensor tech wasn’t as mature, maybe the full time live view had a negative impact. Either way, the R1 only matched rival DSLRs on resolution and noise at low sensitivities, and lost out as the ISO became higher.

It’s also worth noting the R1’s large sensor with its correspondingly large low-pass filter meant there was no way to move it out the way to implement the Nightshot modes of the later F series. So if you want to shoot in darkness or try out infra-red magnet hacks, the Cyber-shot F828 remains your best bet.

Sony Cyber-shot R1 verdict

The Cyber-shot R1 was Sony’s first high-end all-in-one since the F828 two years previously, and not only banished the purple fringing which plagued that model but finally equipped this series with the large sensor it always deserved. Crucially this allowed Sony to compete against the rising tide of budget DSLRs while it prepared the launch of its own Alpha series following the acquisition of Minolta.

The R1 was more than a stopgap though. It was forward-thinking, becoming the first large sensor CMOS camera to deliver live view with the benefits of composing with the screen or viewfinder. Remember this was 2005 and live view on a DSLR, especially one with an APSC sensor, was still a while away.

But while today’s market is dominated by large CMOS sensors, back in 2005 it was still relatively young. I can’t say whether immature technology, full-time live view, or another factor was to blame, but the R1’s images fell behind rival DSLRs in my tests, especially on noise at higher sensitivities. This could have been compensated to some degree with the chance to record video, but Sony didn’t implement it on the R1, reducing its potential advantage over a similarly-priced DSLR.

And while the R1’s zoom range was broader than a DSLR kit lens, the contrast-only autofocus made it less practical for capturing subjects in motion. Meanwhile the lens aperture may have been a little brighter than a DSLR kit lens, but not enough to make any meaningful difference to depth of field.

Indeed once Sony launched its own Alpha series of DSLRs the following year, regular development of high-end fixed-lens models was essentially halted. Sony did occasionally return to the concept with the RX series, and the most recent spiritual successor to the R1 is arguably the RX10 Mark IV from 2017. This may have employed a smaller 1in-type sensor, but greatly expanded the zoom range and for me remains one of their most underrated cameras.

Today models like the Fujifilm X100 series prove there’s still demand for fixed lens cameras with large APSC sensors, and that’s why vintage models like the R1 still command high prices. But the sensor tech in 2005 wasn’t quite there yet, and like Canon’s EOS 5D, I think it’s the assumption of quality, rather than the actual reality which keeps their used prices high. So as much as I wanted to love the R1 then and now, I’d say it’s not worth the typical prices on the used market. Unless you can bag one for less than 75, I’d sooner have a cheaper Cyber-shot F828 with its longer zoom, video recording and infra-red hacks.

Check prices at Amazon, B&H, Adorama, eBay or Wex. Alternatively get yourself a copy of my In Camera book, an official Cameralabs T-shirt or mug, or treat me to a coffee! Thanks!