Panasonic Lumix GM5 review

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

Intro

The Panasonic Lumix GM5 is a mirrorless system camera based on the Micro Four Thirds standard. Announced in September 2014, it’s the successor to the Lumix GM1 launched a year earlier.

The Lumix GM5 shares essentially the same tiny body of the GM1, making it one of the smallest system cameras around, but adds two important new features: first is an electronic viewfinder squeezed into the top left corner as you hold the camera, and second is a hotshoe, allowing it to accommodate a small supplied external flash.

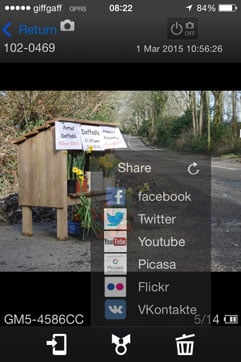

The touchscreen remains, and there’s also built-in Wifi, but like the GM1, no NFC for size reasons. Movies are captured at a maximum of 1080 / 60p, but there’s no 4k video here due to heating issues.

As well as competing with larger compact system cameras the GM5 is up against advanced compacts with larger than average sensors and fixed zoom lenses with a bright focal ratio. Here I’ve compared the GM5 with Sony’s RX100 III and Panasonic’s own Lumix LX100 and tested it to see how it compares with two larger compact system cameras – the Olympus PEN E-PL7 and Samsung’s NX300.

Lumix GM5 design and controls

The Lumix GM5 measures 99x60x36mm and weighs 211g with battery, making it a little taller and thicker than the original, but unless you have them side by side it’s hard to see any significant difference. It’s still an extremely small camera, and also available with a smart red finish in addition to the standard black.

You realise just how tiny the GM5 is when you see it alongside a comparatively chunky compact system camera like the Olympus PEN E-PL7. The E-PL7 measures 115x67x38mm and weighs 357g with a card and its battery fitted. And the GM5 is also dwarfed by the Samsung NX300 which measures 117x66x39mm. Both the PEN and the NX3000 have flip out screens which is one of the reasons for their extra bulk, and the Olympus boasts built-in stabilisation too, however neither has a built-in viewfinder.

|

Though the Lumix GM5 may win in a compactness contest with other mirrorless system cameras, its not such a walkover when it comes to the advanced fixed lens compacts which it also competes with.

Of course as an interchangeable lens camera, you’ll need to add a lens to those specifications to come up with a working comparison to a fixed lens model. Panasonic bundles it with the 12-32mm f3.5-5.6 (24-64mm equivalent) zoom first seen with the GM1, which adds 24mm to the overall thickness and brings the combined weight to 281g. Compare that to Sony’s RX100 III which has a built-in viewfinder and a lens offering a 24-70mm equivalent focal length and an aperture of f1.8-2.8. The RX100 III measures 102x58x41mm and weighs 290g with battery, so it’s clear to see the Lumix GM5 is in the same ball park for size and weight. The sensor in the Sony RX100 III is smaller, but its lens is brighter than the Lumix kit zoom, allowing it to deploy lower ISOs under the same light levels – indeed the brighter lens pretty much cancels out any advantage of the GM5’s bigger sensor. But the RX100 III’s lens is fixed, whereas the GM5’s key advantage is being able to swap lenses and enjoy access to the broad Micro Four Thirds catalogue. Panasonic also produces lenses designed to complement the size of the GM series and not protrude beneath the base of the camera (important when mounting on a tripod): along with the 12-32mm, there’s a new 35-100mm f4-5.6 that’s tiny, and for those who want a classy but compact prime, there’s the Leica 15mm f1.7.

The other fixed lens compact that’s likely to draw custom away from the GM5 is Panasonic’s own Lumix LX100. With a 24-75mm equivalent f1.7-2.8 lens it measures 115x66x55mm and weighs 398g, so again, the GM5 with its 24-64mm (equivalent) removable lens compares favourably on size and weight. Interestingly the LX100 also employs a Micro Four Thirds sensor, but the lens doesn’t quite use all of it, giving the GM5 a minor advantage in usable sensor area. But again the LX100’s lens is comfortably brighter across the range, more than compensating for the slightly cropped sensor area. So once again you have to decide if you’ll exploit the removeable lens benefit of the GM5. If you’re unlikely to remove the 12-32mm kit lens, then you may be better off with the RX100 III or LX100.

|

Back to the GM5 review. While the top of the original GM1 was flat across its full length with the three controls perched on top, the GM5’s upper panel is on two levels: it dips down a little to meet the control dials so that their height becomes flush with the rest of the body. This lends it an attractive style, but importantly means the dials enjoy a little more protection when the camera’s being removed from pockets or bags.

The top surface is also home to a new hotshoe, a feature lacking on its predecessor. The inclusion of a hotshoe and an EVF though means there’s no longer room for a popup flash on the GM5, although Panasonic does bundle it with a small unit that clips onto the hotshoe. This puts in on the same footing as both the Olympus PEN E-PL7 and the Samsung NX3000, both of which come with an accessory flash in the box. The LX100 also doesn’t have a built-in flash, but Sony’s RX100 III does have one.

There’s no denying a built in flash is a more convenient option than a clip on one, the chances are you won’t have it with you on the rare occasions it might be of some use. You could argue there’s no point adding size and weight for an accessory that doesn’t get used that often, ultimately it’s a personal preference, you’ll have to decide whether you do enough flash photography for it to make a difference, although if that’s the case, the ability to plug in a bigger more powerful flash is also a big advantage.

The new EVF on the GM5 delivers a very small, but thankfully detailed image, similar in size to that on the LF1 and TZ60 / ZS40, but much better quality. The first time you look through it, you’ll think it’s small, but you quickly become used to it. The viewfinder panel is 4:3 shaped, so matches the native aspect ratio of the camera. The panel resolution is 1166k dots with 0.46x magnification, making it both smaller and slightly lower resolution than the EVF on the RX100 III, although in its favour, the GM5’s is always ready to go, whereas on the Sony you need to pull-out the housing first.

A small sensor with adjustable sensitivity located to the right of the EVF automatically activates it when you put your eye to the viewfinder and when this happens the touch screen is deactivated and goes blank. This is the most convenient configuration but if you’d rather have manual control you can switch between the monitor and viewfinder for composition using the Fn2 button. Of course if you do that you lose a function button, but there’s one other physical Fn button (the default Wifi button) plus no fewer than five touch screen Fn buttons, making seven in all, and with a dial for AF mode, and ISO sensitivity, white balance, drive mode and focus area on the four-way controller, you’re not likely to miss it.

In order to accommodate the viewfinder without making the camera too much taller, Panasonic has fitted the GM5 with a shorter, wider screen on the back. It’s still 3in across the diagonal, and still touch-sensitive, but is now 16:9 shaped rather than 3:2.

Both the viewfinder and monitor can be set to display an information overlay with or without a 2-axis level . You can also display the overlay on a black band below the picture area though why you’d choose to make what’s already a comparatively small view of the image tinier still is a bit of a mystery. The GM5’s 16:9 screen is a poor match for its 4:3 images which are displayed with a large black band down either side, though this is put to good use on the right side for a pop-out panel of touch buttons. On the positive side, the 16:9 is perfectly proportioned for movie shooting.

If you’re using the GM5’s electronic viewfinder for composition, probably the best use for the the screen is to set it to display info. Program mode, exposure information, AF mode, image quality, metering mode and card capacity, among other things are all displayed in big, easy to read panels some of which can be set using the touch-screen. Controls and accessibility are so often casualties of miniaturisation, it’s a pleasant surprise to discover that in this configuration the GM5 gives you direct access to pretty much any setting you’re likely to need.

The GM5 also ditches the rear flat wheel of the GM1 in favour of a dial positioned to the right of the EVF. The dial is chunky, tactile and includes a push-click operation like earlier Panasonic models. It’s far preferable to the thumb wheel on the GM1 that I constantly pressed by accident when trying to turn it. The new rear dial is a big improvement in ergonomics.

The GM5 uses the same 680 mAh battery as its predecessor which, with the 12-32mm kit lens fitted, provides enough power for 210 shots when composing with the monitor. If you primarily use the viewfinder to compose there’s a bonus of 10 additional shots in it. This is pretty meagre by any standards. The Sony RX100 III manages 320 shots per charge as well as the advantage of in-camera charging via USB. In-camera USB battery charging is also a feature of the Samsung NX300 which will go for 370 shots on a full charge and though the Olympus PEN E-PL7 has an external mains charger like the GM5, its battery will last for 350 shots.

The RX100 III is a fixed lens compact and the two compact system cameras are of course bigger and heavier than the GM5 and, so the GM5 arguably offers a reasonable deal in terms of the trade-off between size and battery life, but it’s very short life span pretty much dictates carrying a spare, particularly if you plan on shooting video, using the interval timer, or making use of the built-in Wifi.

Lumix GM5 lens and stabilisation

The Lumix GM5 may look like a fixed-lens compact, but it is in fact a fully-fledged system camera with a Micro Four Thirds mount, which gives it access to the broadest native lens catalogue of any mirrorless system – and of course multiple third party lenses via adapters. This is one of the key advantages it has over fixed lens models like the Sony RX100 III and Lumix LX100.

It is however important to remember the GM5 is a very small camera with little to hold onto unless you buy the optional grip. As such it’s much harder to hold comfortably or steady for any length of time when using anything other than the kit zoom, you may also experience problems mounting it on a tripod when using other lenses due to their barrels extending below the camera’s base.

Panasonic designed the new 12-32mm kit zoom specifically for the original GM1, and it’s truly a marvel of optical engineering. It’s incredibly light and measures just 24mm thick to match the diameter of the lens mount on the body so it’s hard to tell where one starts and the other ends; this also means the bottom of the lens is flush with the camera body and therefore avoids any issues with all but the largest tripod plates. The zoom ring is also positioned on the outer edge, again minimizing any tripod trouble.

Lumix GM5 with 12-32mm wide | Lumix GM5 with 12-32mm tele | |

|  | |

| 12-32mm at 12mm (24mm equiv) | 12-32mm at 32mm (64mm equiv) |

The lens is a collapsing design that must be extended for use. There’s no lock, you simply give the zoom ring a firm twist and an inner barrel pops out, roughly by the same amount again; the zoom ring then starts at 12mm and rotates round to 32mm.

While it’ll take you a second or two to unclip the lens cap, you can at least twist the zoom ring very quickly and arrive at the longest focal length in under a second. In contrast, the Sony RX100 III takes over two seconds to activate its built-in zoom and the Samsung NX3000’s powered kit zoom takes a similar amount of time. The Olympus PEN’s powered 14-42mm kit zoom is comparatively swift and the E-PL7 can take a shot in a fraction over one second after you’ve pressed the power button. But the GM5 still has the edge if you want to zoom in as you just extend the twisting action which takes no time at all. Zooming the Olympus 14-42mm EZ lens to its maximum extent adds another couple of seconds to the time taken.

The 12-32mm is such a good match for the GM5 that it’s fair to believe many owners will rarely if ever remove it. Indeed in some regions, Panasonic is even marketing the kit as if it were a fixed lens compact, so it’s important to see how its capabilities compare to the competition.

Above you can see the coverage of the 12-32mm kit zoom, which delivers a 24-64mm equivalent range thanks to the two-times field reduction factor of the Micro Four Thirds system. The 2.6x total range is only slightly less than the 3x ranges of typical 14-42mm or 18-55mm kit zooms, but satisfyingly starts at a wider 24mm equivalent compared to around 28mm as the norm. As we’re comparing the GM5 with another Micro Four Thirds model and an APS-C camera with a 1.6x field reduction factor it’s simplest to compare equivalent focal lengths. So at the wide angle end of the range the GM5 provides 24mm compared with 28 on both the PEN E-PL7 and Samsung NX300 kit zooms. At the telephoto end it’s 64mm compared with 84mm on the E-PL7 and 75mm on the NX3000. All three kit lenses share the same f3.5-5.6 focal ratio.

But if the GM5 is also competing against fixed lens compacts, it’s important to compare their lens specifications carefully. So to re-iterate, the GM5’s 12-32mm kit zoom offers a 2.6x / 24-64mm equivalent range with an f3.5-5.6 focal ratio. Sony’s RX100 III has a 2.9x / 24-70mm equivalent range with an f1.8-2.8 focal ratio and Panasonic’s LX100 has a 3.1x 24-75mm range with an f1.7-2.8 focal ratio. As I mentioned earlier, the brighter lenses on the RX100 III and LX100 effectively compensate for their smaller active sensor areas, so don’t go choosing any of these cameras based on sensor size alone. The main reason you’d go for a camera like the GM5 over the RX100 III or LX100 is for the chance to swap lenses.

The GM5 has an interchangeable lens mount that’s compatible with the Micro Four Thirds standard. Micro Four Thirds, jointly developed by Panasonic and Olympus, is the most established of the mirror-less system camera formats, bringing bodies and native lenses to the market at least one year before its first rival arrived. Being first to market along with having not one but two major manufacturers behind it are two major advantages Micro Four Thirds enjoys over the competition, and it really shows when you compare their respective native lens catalogues.

As of early 2015, Micro Four Thirds had over 50 lenses available from Panasonic and Olympus along with third parties including Sigma, Tamron, Samyang, Voigtlander and others. So while many rival mirror-less formats are struggling to offer even one lens in every category, Micro Four Thirds typically has two or more options available. Whether it’s Fisheye, ultra wide, fast aperture, macro, super-zoom or good old general-purpose, the Micro Four Thirds catalogue has it covered, and many of them are great quality too – find out more in my Micro Four Thirds lens guide.

The ability to mount a wide variety of lenses on the GM5 is a big advantage it enjoys over rival compact cameras like the Sony RX100 II and Lumix LX100, but it’s not all roses. Since the 12-32mm kit zoom is just about the smallest lens in the catalogue, almost any other model will look and feel quite large when mounted on the tiny GM5 body. Annoyingly most of the lens barrels protrude below the base of the GM5’s body which makes it hard to mount them on a tripod. So while the GM5 can swap lenses, I wonder how many owners will exploit it on a regular basis; I suspect most will stick with the 12-32mm kit zoom, although it is at least nice to have the option to fit others if desired.

Panasonic Lumix GM5 Mega O.I.S: Off / Normal | ||||

|  | |||

100% crop , 12-32mm at 32mm, 200 ISO, 1/8, O.I.S off. | 100% crop , 12-32mm at 32mm, 200 ISO, 1/8, O.I.S Normal. | |||

The Lumix 12-32mm f3.5-5.6 features Panasonic’s Mega O.I.S images stabilisation. To put it to the test I zoomed it into its longest focal length and took a series of photos with and without stabilisation enabled at progressively slower shutter speeds.

As you can see from the 100 percent crops above, enabling stabilisation allowed me to handhold a sharp result at 1/8, which means the system was delivering three stops of compensation. This isn’t as great as some of the systems I’ve tested, but a factor in successful handholding is without a doubt how easily you can hold the camera body steady to start with – and in this respect the GM5’s’s very small dimensions and light weight don’t do it any favours. I had to make several attempt to get one sharp shot at 1/8 and could only get consistent results at 1/15. That said, three stops of compensation is still very useful to have.

Lumix GM5 movie modes

The Lumix GM5 inherits all of the movie modes of it’s predecessor along with the addition of a new 1080 / 50p / 60p mode. This was apparently disabled on the GM1 due to concerns of overheating, but I can report that it wasn’t an issue with the new model. When shooting for longer than a couple of minutes the body becomes warm, but not hot.

Set the Lumix GM5 to AVCHD encoding and you can choose from 1080 at 60p, 60i, or 30p for NTSC regions, or 50p, 50i, or 25p for PAL regions. The interlaced modes are encoded at 17Mbit/s with the 60p / 50p and 30p / 25p modes encoded at 28Mbit/s and 24Mbit/s respectively. Regardless of region you can alternatively choose a 1080 / 24p option at 24Mbit/s.

Alternatively the Lumix GM5 can encode videos in the MP4 format for easier editing, with the choice of 1080 / 60p / 50p at 28Mbit/s, 1080 / 30p / 25p at 20Mbit/s, 720 / 30p / 25p at 10Mbit/s, or VGA 30p / 25p at 4Mbit/s. Again those frame rates are region dependent.

Like earlier models, the Lumix GM5 offers the choice of single or continuous AF modes, along with the option to pull-focus by simply tapping the subject on the touch-screen. The GM5 inherits focus peaking from its predecessor, which surrounds subjects that are in focus with a coloured fringe. This makes it much easier to manually focus as you’ll know exactly when to stop adjusting the focus as the subject becomes highlighted. Though the kit lens lacks a focus ring, manual focussing using screen controls in combination with the peaking feature proved surprisingly effective.

Audio is recorded using built-in stereo microphones either side of the hot shoe on the upper surface and it’s possible to set the recording levels manually if desired, and if you like, also display mini peak level meters in the corner of the screen. Sadly there’s no chance to fit an external microphone though, unlike the PEN E-PL7.

The Lumix GM5 offers full manual control over movie exposures, with PASM modes. You can adjust the aperture, shutter or sensitivity (the latter between 200 and 3200 ISO), and even make silent adjustments while filming, using on-screen sliders if preferred At the other end of the spectrum Panasonic has introduced the snap movie feature which records a short clip of between two and eight seconds in length. With snap movies you can set up a focus pull in advance tapping the screen to define the start and end focus positions, which is pretty neat. You can also add a monochrome to colour fade in our out effect, which is nice, but a simple exposure fade might have been more useful.

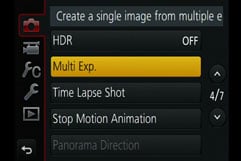

As before you can start and stop recording by pressing the dedicated red button on the rear. You can take photos while filming which share the same aspect ratio as the video, and with the choice of two quality options: if you don’t want the stills to interrupt the video, they can only be saved in a small size, but if you prefer a large version, it’ll temporarily blank the recording. Also inherited from the GM1 are Time Lapse and Stop Motion modes, accessed through the main menus rather than the movie options.

These can automatically assemble a movie from a sequence of still photos, either taken automatically by the camera at preset intervals, or manually as and when you’re ready. The auto mode is ideal for making time-lapse films, although the manual Stop Motion option allows you to create your own animated movies using drawings or models for example. Once you’ve finished capturing your photos, the camera can then encode them into an MP4 movie at your desired resolution and frame rate, although note it will inherit the original aspect ratio of the photos and won’t crop 4:3 to 16:9, so if you’re wanting a widescreen movie, don’t forget to set the photo aspect ratio to 16:9 first.

Just before sharing more movie samples, it’s worth making some comparisons with the GM5’s closest rivals. The RX100 III can film 1080p at 50p and 25p for PAL regions or 60p and 24p for NTSC regions and it also provides the opportunity to record in the XAVC S format at a higher bit rate of 50Mbit/s. There’s also a high speed 120fps mode which can be edited to play back at quarter speed. Like the GM5, the RX100 III also offers PASM exposure modes.

Neither the PEN E-PL7 nor the Samsung NX300 offer a 1080 mode at 50p or 60p, both offering 1080 at 30p in two quality settings. Like the GM5 they both provide PASM exposure control for movie shooting, and like the GM5 the PEN allows you to pull focus by tapping its touch-screen.

The Sony, Samsung and Olympus offer motorized zooms as standard (fixed in the case of the Sony RX100 III), whereas the GM1’s kit zoom is manually operated. All four models have a built-in hotshoe, but the GM5 is limited to its built-in mics where the Olympus can accommodate an external microphone accessory.

The GM5 and PEN E-PL7 allow you to apply the popular miniature effect to movies, but the RX100 III and NX3000 do not. The Samsung NX3000 is the only one of the four not to offer focus peaking and on the GM5, and RX100 III focus peaking remains active when recording.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

Lumix GM5 Shooting Experience

The Lumix GM5 is quick out of the blocks. With the 12-32m kit lens fitted it’s ready to shoot in a little over a second after you’ve switched it on. That’s important because the short battery life means you can’t really afford to wander around with it switched on when you’re not actively shooting. Though it does have an economy feature which puts it to sleep after a preset time period has passed.

The GM5 has inherited the sophisticated AF modes and capabilities of its predecessor. Most importantly, the GM5 offers 240fps AF drive for quicker response (on supported lenses), and usefully it can now also autofocus in dim light conditions down to -4EV. Like the GM1 before it, the GM5 will quite happily autofocus, even with a tiny AF area, under very dim conditions. The 240fps drive means the GM5 is also very quick in better light, especially with lenses which support it like the 12-32mm kit zoom. Fitted with the 12-32mm for most of my tests, the Lumix GM5 snapped onto the subject almost the instant I half-pressed the shutter release.

| |||

Like earlier models, the touch-screen also makes it easy to tap on the subject you’d like to focus on, and it’s now even simpler to adjust the size of the AF area using the new rear thumb dial. By dialing this down to a tiny square it’s possible to just tap the closest eye on portrait shots. However, the introduction of face/eye detection makes this largely unnecessary.

With Face/eye AF area mode selected the GM5 frames faces in the frame with a rectangle and when it’s able to it locks focus on the eye closest to the camera – indicating this with a pair of intersecting fine lines. For portraits it’s invaluable and its fairly solid, though in low light the GM5 sometimes struggles to lock focus on the nearest eye and when it does tends to stay with it even when your subject alters position. When that happens there’s a simple solution, though, you just tap the screen to select the eye you want to focus on. The GM5 also has the eye sensor AF feature, whereby the AF is activated when you put your eye to the viewfinder.

One of the drawbacks of the 12-32mm zoom though is that you need to position subjects a long way in front of any background you want to blur. As you can see from the shot above, with the lens zoomed into 64mm equivalent and wide open at f5.6 the depth of field isn’t all that shallow. It is possible to throw the background out of focus, you just have to get close enough to your subject and keep the background reasonably distant. The closest focussing distance of the 12-32mm kit lens is 30cm at the 32mm focal length and that’s about as close as I was to the porcelain figure in the shot below..

Panasonic's Lumix GM5 is a tiny mirrorless system camera based on the Micro Four Thirds standard - so while it's roughly the same size as a Sony RX100, it actually supports interchangeable lenses. The GM5 builds on the existing GM1 by packing in a small but detailed electronic viewfinder, a hotshoe and a new control dial on the rear that greatly improves ergonomics over the original. As before there's also a touch-screen, Wifi (but no NFC) and 1080p video up to 60p.

Panasonic's Lumix GM5 is a tiny mirrorless system camera based on the Micro Four Thirds standard - so while it's roughly the same size as a Sony RX100, it actually supports interchangeable lenses. The GM5 builds on the existing GM1 by packing in a small but detailed electronic viewfinder, a hotshoe and a new control dial on the rear that greatly improves ergonomics over the original. As before there's also a touch-screen, Wifi (but no NFC) and 1080p video up to 60p.