Panasonic Lumix 7-14mm f4 review

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

Intro

The Panasonic Lumix 7-14mm f4 is an ultra-wide angle zoom lens for Micro Four Thirds cameras, including Panasonic Lumix G, Olympus PEN and Olympus OMD models. Mounted on a Micro Four Thirds body it delivers an effective focal length of 14-28mm, covering most of the popular wide-angle focal lengths from mild to extreme, while the f4 aperture remains constant throughout the range.

Launched in March 2009 it was actually only the third Micro Four Thirds lens from Panasonic, making it the first truly exotic lens for the mirrorless format. It carried – and continues to carry – a relatively high price tag, albeit not as much as the Olympus 7-14mm f4 lens which preceded it for the full-sized Four Thirds system.

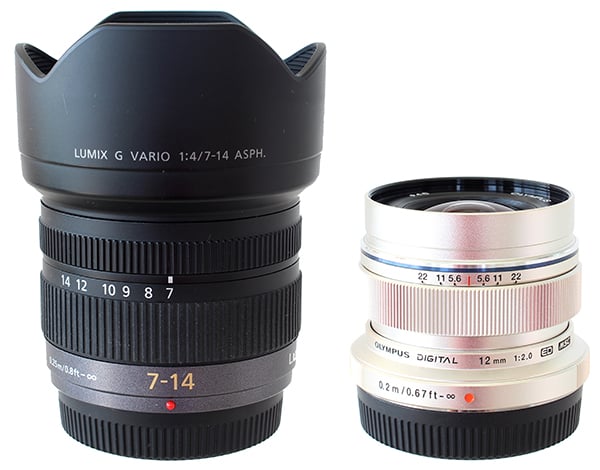

At launch it was the only native ultra-wide zoom for Micro Four Thirds cameras, although it has since been joined by the more affordable Olympus 9-18mm f4-5.6, along with a number of wide angle primes including the Olympus 12mm f2. In my Panasonic 7-14mm review I’ll take an in-depth look at the performance of this lens and how it compares to other options in the Micro Four Thirds catalogue. In my optical tests I’ll also show you how it compares to the Olympus 12mm f2, and I plan to update the review at a later date with further comparisons with the Olympus 9-18mm zoom.

Panasonic 7-14mm f4 design, build quality and focusing

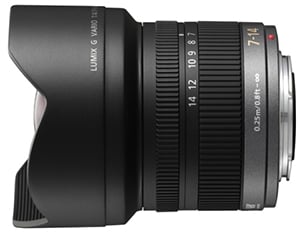

The Panasonic Lumix 7-14mm f4 physically resembles many ultra-wide zooms for other systems with a barrel that becomes steadily wider towards the front before ending with a bulbous element protected by a built-in petal lens hood. So far so like the Olympus 7-14mm f4 and the Nikon 14-24mm f2.8, although the thing which makes the Panasonic unique in this group is its size and weight.

The Panasonic 7-14mm f4 is 83mm long, has a maximum diameter of 70mm at the front and weighs 300g. The older Olympus 7-14mm f4, which shares the same aperture and sensor format measures 120mm in length with a fairly constant diameter of 87mm and a weight of 780g. That’s 50% longer, 20% wider and about two and half times heavier, although it does sport dust and spashproof sealing which the Panasonic sadly does not.

Moving onto larger formats, the Nikkor 14-24mm f2.8 measures 132mm in length, 98mm at its widest diameter and weighs 970g. That’s almost 70% longer, 50% wider and over three times heavier. Now to be fair the Nikkor lens sports an aperture that’s twice as bright as the Panasonic and optics that are corrected for a full-frame sensor that’s four times the area of Micro Four Thirds, but if your priority is carrying the most compact ultra wide kit, it makes for an interesting comparison.

|

So for fun I mounted the Nikkor 14-24mm onto a Nikon D800 body and photographed it next to the Panasonic 7-14mm mounted on a GX1 body. Again the Nikon combination is weather-sealed, boasts a sensor that’s higher resolution and four times larger, sports a lens with one stop greater light gathering power and a potential depth of field that’s two stops shallower, but the total weight is 30g shy of 2Kg compared to 618g for a GX1 with the 7-14mm, yet they share essentially the same coverage and in terms of size, the picture opposite speaks for itself. And while the Nikkor lens doesn’t actually cost that much more than the Lumix 7-14mm, the price of even an entry-level full-frame body to mount it on makes the working combination much more expensive.

For many photographers though the resolution and even the price isn’t the main issue, it’s the size and weight that makes or breaks a deal. For example I needed a compact but high quality three-lens kit to take with me traveling for an extended period and simply couldn’t accommodate a full-frame body with even one lens, let alone three. For that reason I chose the Panasonic GX1 with the Lumix 7-14mm along with the Leica 25mm f1.4 and the Leica 45mm f2.8, which I later swapped for the Olympus 45mm f1.8. This body and three lens kit fitted into less space than a D800 with a 14-24mm and still weighed at least a third less. However much I love the D800 (or D600) with the 14-24mm, it was a no-brainer for me and a decision I never regretted during nine months of travel.

As I mentioned earlier, the Lumix 7-14mm isn’t the only ultra-wide option for Micro Four Thirds owners. The main competition comes from the newer and more affordable Olympus 9-18mm f4-5.6, which doesn’t quite get as wide, but does zoom a little longer. The aperture starts at the same f4, but becomes a stop slower than the Panasonic by the time it reaches its longest focal length. It is smaller and lighter than the Panasonic though, measuring 50mm in length, 57mm in diameter and weighing only half as much at just 155g. Beyond costing around one third less, one of the other big selling points of the Olympus over the Panasonic lens is its ability to accommodate standard 52mm filters, whereas the 7-14mm has no built-in solution at the front or rear. I hope to directly compare the optical quality of both lenses at a future date and will supplement this review with the results.

If you want wide angle coverage with a brighter aperture, another option is the Olympus 12mm f2 prime lens which I’ve pictured next to the Panasonic here. This has a fixed focal length with coverage that’s equivalent to 24mm and an aperture that’s two stops brighter than the Panasonic 7-14mm, making it preferable in low light. It’s also unsurprisingly smaller than the Panasonic, measuring 43mm in length, 56mm at its widest diameter and weighing just 130g. It’s cheaper too, but only by about 25%, unless you opt for the surprisingly expensive limited edition black version.

|

I was particularly interested to see how the optical quality of the Olympus prime compared to the Panasonic at the same 12mm focal length, and in my results pages you’ll find out! You’ll also see how the 7-14mm compares against a typical kit zoom when both are set to 14mm, along with how the 7-14mm measures-up at 10mm and 7mm. You can jump straight to my Panasonic 7-14mm quality pages if you can’t wait, but if you stick around a bit longer I’ll tell you more about the physical side of the lens along with its AF performance and any issues to be aware of.

For a lens which costs the best part of $1000 USD, the Panasonic Lumix 7-14mm has a surprisingly ordinary exterior and mechanical construction. Ignore the bulbous front element and built-in lens hood and it most closely looks and feels like, gulp, a kit lens. To be fair the lens mount is metal, the zoom ring is reasonably well-damped, and thanks to a heavier weight than most kit lenses, it feels more solid in your hands, but there’s no denying the plasticky look and scratchy manual focusing ring are out of place for a lens of this price.

|

|

|

With this in mind it’s no surprise to learn the 7-14mm isn’t weather-sealed either. As one of the earliest lenses for the Micro Four Thirds format, the 7-14mm missed out on the environmental sealing we’re only beginning to see on a handful of top-end lenses for the format. Panasonic would argue there weren’t any weather-sealed Micro Four Thirds bodies back then, but it’s pretty short sighted to assume this was always going to be the case. Surely it would have been better to simply equip all the top-end lenses with environmental sealing from day-one – then fast-forward to 2012 and owners of the Olympus OMD EM5 and Panasonic GH3 would be able to enjoy a classic lens with full weather-sealing. As it is, like so many cracking older Micro Four Thirds lenses including the Leica 25mm f1.4 and 45mm f2.8, the 7-14mm cannot confidently be used in tough conditions. I should note the lens and GX1 survived a day of constant drizzle during a trip I had through Iceland, but I wasn’t happy about exposing them to these conditions.

In many respects, the approach behind the Lumix 7-14mm lens reminds me of Canon’s higher-end EF-S lenses like the 10-22mm. Optically it’s very strong with a price tag to match, but physically it’s disappointingly non-luxurious.

In better news, the zoom ring is well-damped so there’s no chance of it slipping, and you’ll rarely need to use the manual focusing ring on a lens this wide. I should also again note the 7-14mm is heavier than a kit lens, so feels denser and more solid. It doesn’t rattle or creak either, but just don’t expect too much in the design and mechanical department.

As you can see in the photos, the 7-14mm widens towards the front where the barrel finally turns into a built-in lens hood constructed with thick plastic. Within the hood, the bulbous front element raises or lowers slightly as you zoom through the range, but always stays well-protected from both flare and glancing knocks. The hood is really well designed and while you’ll initially feel the front element is vulnerable, you’ll soon realize it’s actually very well protected. I put this lens through a lot during a year of travel and after only a few days stopped worrying about the safety of the front element. Meanwhile, a supplied ‘cap’ slides over the hood and stays firmly in place through friction. This is well built and never fell off during a year of daily use.

Like many ultra-wide lenses though, the 7-14mm does not feature any kind of filter mount, whether on the front or with some rear-mounting solution. At first this may seem like a big loss, although in a year of heavy use I never needed the protection of a filter due to the well-designed lens hood, and I never missed having a polarizer due to their often undesirable results on an ultra-wide lens. But for some it will remain a big issue and they’ll either need to buy or construct a filter holder for it, or consider the Olympus 9-18mm instead, which sports a filter mount.

The optical design employs 16 elements in 12 groups with two Aspherical lenses and four ED lenses – as an older model it precedes Panasonic’s use of Nano coatings to reduce flare. The closest focusing distance is 0.25m from which it’ll deliver a maximum magnification / reproduction of 0.08x. The aperture is controlled by a seven-blade diaphragm with rounded blades. There’s no optical stabilization, which means owners of Panasonic bodies will need to keep sufficiently steady or use a fast enough shutter speed to avoid camera shake – this will rarely be an issue for stills at ultra wide focal lengths, but for video you can still see shake even at 14mm equivalent so for the sake of shaky videographers everywhere I wish Panasonic would just build stabilization into every lens. You could of course mount it on an Olympus body and enjoy the built-in stabilisation, but please be aware of the compatibility issues noted below.

In terms of autofocusing, the 7-14mm feels pretty quick and is virtually silent, but then as an ultra-wide lens with a massive effective depth of field it doesn’t exactly have a lot of work to do in that department.

In terms of optical issues, you’ll want to shoot close to the maximum aperture to avoid diffraction. As you’ll see in my Panasonic 7-14mm quality pages, the results are thankfully very good even wide open at f4, with only some vignetting apparent on uncorrected images, but that’s easily removed digitally, or optically by closing to f5.6. But I would avoid anything smaller than f8 for the crispest results. Remember you’ll still have a massive depth of field even at f5.6, as in full-frame terms, that’s equivalent to f11 which on a 14-28mm effective focal length will deliver a lot that’s in focus.

Some photographers also use ultra-wide lenses to shoot directly into the Sun and render it into a starburst by closing the aperture down. I tried this several times on the 7-14mm without much success though, and ended up with a disappointing looking Sun and an overly soft image due to diffraction. If you intend to use this lens for Sun starbursts, you should investigate further to see what others have achieved as it could have been down to my test sample or the conditions I was shooting in.

Like other Micro Four Thirds lenses, a number of corrections are made for the optics automatically. Geometric distortion is automatically corrected on JPEGs when mounted on Panasonic or Olympus bodies, and also by most popular RAW converters like Adobe Camera RAW. Chromatic aberrations from Panasonic lenses are corrected automatically on Panasonic bodies, but not those from Olympus (until the EM1), so owners of all but the latest Olympus bodies may wish to shoot in RAW and remove them in software later. Meanwhile vignetting, which is only really an issue at f4, can easily be corrected in software.

Just before wrapping-up this section, I wanted to discuss a lens compatibility issue involving the Panasonic Lumix 7-14mm and a number of Olympus bodies including the OMD EM5 and EM1. When this lens is used with Olympus bodies, images can sometimes suffer from purple flare artefacts which in some cases can be quite distracting and hard to retouch. It most commonly occurs when your image includes small but bright lights against a dark background, such as an interior at night or a city night-scene. Interestingly though, the effect is much less of a problem with Panasonic Lumix bodies, implying some difference in sensors.

To see if I could trigger and compare the effect, I took the same composition with the OMD EM1, OMD EM5 and Lumix GX7 to see if there were any differences. I took care to include a bright light to accentuate the effect. Each camera was mounted to a tripod and fitted in turn with the same Lumix 7-14mm lens, set to 7mm f4 in Aperture Priority mode. All three cameras were also set to exactly the same exposure. Below are the three images with crops of the affected areas below – the crops are taken from the same area, marked by the red rectangle on the image below left.

Olympus OMD EM1 using Panasonic Lumix 7-14mm | Olympus OMD EM5 using Panasonic Lumix 7-14mm | Panasonic Lumix GX7 using Panasonic Lumix 7-14mm |

|  |  |

Full image | Full image | Full image |

|  |  |

100% crop showing affected area | 100% crop showing affected area | 100% crop showing affected area |

As you can clearly see, the newer OMD EM1 suffers to exactly the same extent as the EM5 before it, exhibiting quite dramatic purple blobs on the image. To be fair in this particular example they’re quite well hidden when viewed at lower magnifications, but I have seen other situations where the purple artefact has been visible even with the image viewed on the camera’s screen without zooming-in. It can be a real issue if you’d like to shoot bright lights with this lens on an Olympus body.

Interestingly while many owners of Olympus bodies and this lens have reported the issue, most people have assumed Panasonic bodies avoid it altogether. As you can see from the GX7 crop though, this is not the case – the same flare blobs are present on the image when you know where to look, but crucially they’re much less noticeable. As far as I understand this isn’t down to digital correction, but more likely a difference in filtering on the sensor – as both Olympus and Panasonic use different sensors.

It’s a shame the Lumix 7-14mm suffers from bad flare as it is otherwise an excellent lens – indeed one of the sharpest ultra-wide zooms I’ve tested. But the noticeable artefacts when mounted on Olympus bodies, including the new EM1, means anyone considering this combination should go into it with their eyes open to the issue – and if you often shoot night scenes or interiors you may be better off with the slightly less wide Olympus M.Zuiko Digital 9-18mm instead. As for owners of Panasonic bodies though, I think the flare artefacts are sufficiently hard to see to not be a major problem – I’ve certainly shot with the Lumix 7-14mm on Panasonic bodies for many years without issue and it remains one of my favourite lenses. I should also add some enthusiasts have reported success at reducing the effect on Olympus bodies by fitting a special filter on the rear – this doesn’t get rid of the blobs, but it does dull their colour to be less obtrusive.

Now it’s time to take an in-depth look at my results and comparisons. I’ll start by looking at the sharpness of the 7-14mm in the middle and corners at 7mm, 10mm and 14mm before comparing it to the Olympus 12mm prime at 12mm, and the Panasonic 14-42mm Power Zoom kit lens at 14mm. You’ll find it all in my Panasonic 7-14mm quality results pages.

Owners of Micro Four Thirds cameras have the choice of three ultra wide zooms and I think there's merit in recommending all of them. I'll will start with Panasonic's Lumix G 7-14mm. With an equivalent range of 14-28mm and a constant aperture of f4, this is a very classy operator which delivers excellent results across the frame even at the maximum aperture. It features a built-in lens hood which does a good job at protecting the bulbous front element from knocks, scratches as well as stray light. On the downside there's no way to fit filters without a DIY bracket and owners of Olympus bodies may suffer from purple flare when shooting bright lights. But priced between the less extreme Olympus 9-18mm and the higher-end Olympus 7-14mm f2.8, it remains a popular choice and a personal favourite.

Owners of Micro Four Thirds cameras have the choice of three ultra wide zooms and I think there's merit in recommending all of them. I'll will start with Panasonic's Lumix G 7-14mm. With an equivalent range of 14-28mm and a constant aperture of f4, this is a very classy operator which delivers excellent results across the frame even at the maximum aperture. It features a built-in lens hood which does a good job at protecting the bulbous front element from knocks, scratches as well as stray light. On the downside there's no way to fit filters without a DIY bracket and owners of Olympus bodies may suffer from purple flare when shooting bright lights. But priced between the less extreme Olympus 9-18mm and the higher-end Olympus 7-14mm f2.8, it remains a popular choice and a personal favourite.