Leica 50-200mm f2.8-4 review

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

In depth

The Leica DG Vario Elmarit 50-200mm f2.8-4 Power OIS (H-ES50200) is a high-end telephoto zoom designed for the Micro Four Thirds system. Mounted on a Panasonic or Olympus mirrorless body, it delivers equivalent coverage of 100-400mm. If you need more reach, it’s also compatible with Panasonic’s 1.4x and 2x tele-converters.

Announced in February 2018, the DG 50-200mm is another collaboration between Leica and Panasonic for the Micro Four Thirds system. Like earlier collaborations between the two companies, the DG 50-200mm is designed and certified by Leica in Germany, and manufactured by Panasonic in Japan. As such it may not be ‘pure’ Leica, but the optical and build quality is of a very high standard. It also becomes the third model in the series to sport a variable f2.8-4 focal ratio, joining the existing 8-18mm and 12-60mm models.

The Micro Four Thirds catalogue already has a variety of telephoto zooms with a similar focal range, but few that aim as high. Indeed the Leica DG 50-200mm’s biggest rival is likely to be the Olympus 40-150mm f2.8 PRO which may not reach quite as far, but boasts a constant f2.8 focal ratio throughout its range. In my in-depth review I’ll closely compare these lenses, from their build quality and autofocus performance, to their quality of rendering and overall sharpness across the frame.

The Leica DG 50-200mm f2.8-4 shares a family resemblance with the earlier Panasonic / Leica collaborations with a smart-looking design, higher gloss finish and distinctive Leica font for labelling. Measuring 76mm in maximum diameter, 132mm in length and weighing 655g / 23oz, it’s fairly compact for a premium lens with an equivalent coverage of 100-400mm; I was also able to transport it standing up in my f-stop Pro ICU too, making it a very practical option to carry around. Panasonic claims the lens is fully weather-sealed, and I used it in light rain without issue.

In terms of controls, the Leica DG 50-200mm sports a manual focusing ring, zoom ring and two switches to set it between AF and MF, and enable or disable the Power OIS stabilisation. You’ll notice the lens lacks the dedicated aperture ring of some previous Leica lenses, although to be fair, these only worked on Panasonic bodies. There’s also no focus limiter, focus hold nor a programmable function button.

The Leica 50-200mm barrel extends as you zoom to longer focal lengths and I’ve pictured it here in its shortest and longest configurations at 50 and 200mm respectively. On my admittedly brand new sample, there was no evidence of zoom-creep when pointing straight up or down, but this may loosen over time.

The Leica 50-200mm is supplied with a substantial lens hood with a bayonet mounting. This can be reversed over the barrel for transportation.

In terms of range and high-end specification, one of its closest rivals is the Olympus 40-150mm f2.8 PRO. This however is a substantially larger lens, measuring 79mm in diameter, 160mm in length and weighing 760g. It most certainly will not stand up in an f-stop ICU and when laying horizontally, it occupied the full-width when mounted on a body. That said, there are physical benefits to the Olympus lens beyond the fact it boasts a constant f2.8 focal ratio throughout the range. It comes supplied with a removeable tripod foot (complete with Arca Swiss dovetail) and the lens hood is quick and easy to deploy by pulling it out from its folded-down configuration, as oppose to the Leica 50-200mm who’s hood must be removed and reversed over the barrel for transportation. The Olympus 40-150mm also sports a manual focusing ring that can be pulled back to reveal a distance scale and hard stops, while the optics employ internal zooming, so the barrel never extends, which in turn means there’s arguably less chance of dust or moisture entering through the barrel mechanism. To me, the manual focusing on the Olympus felt more physically-connected, while the zooming process felt lighter and smoother throughout the range, whereas on the Leica I was more aware of gearing, the barrel’s extension and its impact on balance. Finally it’s worth noting like all Olympus Pro lenses, the 40-150mm f2.8 features a programmable function button that can be configured on Olympus bodies.

For the record, here’s both lenses with their hoods deployed.

Leica DG 50-200mm optical construction

In terms of optical construction, the Leica DG 50-200mm f2.8-4 employs 21 elements in 15 groups with two UED, two ED and one UHR element. The maximum focal ratio is f2.8-4, there’s nine diaphragm blades, and a closest focusing distance of 0.75m (for a maximum reproduction of 0.5x).

Mounted on a Micro Four Thirds body, the Leica DG 50-200mm delivers coverage equivalent to 100-400mm, taking you from mild to long telephoto. Here’s an example of the coverage below.

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 50mm (left) and 200mm (right)

And now for comparison, here’s how the coverage of the Olympus 40-150mm looks from the same position. It gives you a small advantage at the wide-end, but misses out on the longer reach of the Leica; that said, if you’re happy to crop and lose some resolution, you can easily match the field of view.

Above: Olympus 40-150mm PRO at 40mm (left) and 150mm (right)

If you’d like more reach, the Leica DG 50-200mm f2.8-4 is compatible with the Leica 1.4x and 2x teleconverters, while the Olympus 40-150mm f2.8 PRO is compatible with the Olympus 1.4x teleconverter. I hope to add some tests and comparisons with teleconverters in the future.

While telephoto lenses typically cry-out for sports, wildlife and distant portraiture – all of which I’ll cover in a moment – a long range can also deliver unique perspectives on landscapes and architecture. In particular it can be fun to photograph a subject from further away with a long lens for a less distorted, square-on perspective. Longer focal lengths also compress the perspective, delivering interesting effects compared to wide angles. Here’s some examples with the Leica DG 50-200mm.

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm (left) and 156mm (right)

Above: An equivalent focal length of 400mm isn’t going to deliver a huge Sun or Moon on the frame, but the result can still be attractive when coupled with some landscape elements. This is an un-cropped image.

The focal ratio varies between f2.8 and f4 depending on your position in the range, and as always I like to note exactly where those differences occur. The lens only operates at f2.8 between 50 and 52mm, closing a tad to f2.9 at 53mm, f3 at 56mm, f3.1 at 59mm, f3.2 at 62mm, f3.3 at 70mm, f3.4 at 76mm, f3.5 at 84mm, f3.6 at 100mm, f3.7 at 116mm, f3.8 at 144mm, f3.9 at 150mm, then losing the full stop to f4 from 179mm to 200mm. Remember the Olympus 40-150mm f2.8 PRO boasts a constant f2.8 focal ratio throughout its range, so is almost a whole stop faster when both lenses are at 150mm.

The long focal lengths available mean it’s possible to enjoy fairly decent blurring behind your subject if you can step-back and zoom-in. Here’s a couple of portrait shots at 88 and 200mm, and while they look fine I’d recommend something shorter and brighter if shallow depth-of-field portraits are your main subjects: ideally the Olympus 75mm f1.8 or one of the 42.5mm / 45mm options.

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 88mm f3.5.

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm f4.

As always, if you can get closer to your subject, you can achieve greater blurring. The closest focusing distance of 75cm doesn’t sound particularly intimate, but with the lens operating at the long-end of its focal range it can fill the frame with fairly small subjects, such as the flower, coffee and beer bottles below.

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm f4 and close to minimum focusing distance.

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm f4 and close to minimum focusing distance.

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 50mm f2.8 (left) and 200mm f4 (right), at minimum focusing distances.

And finally if bokeh blobs are your thing, it’s possible to achieve some huge shapes at the long-end of the focal range, again especially if your subject is close. Here’s an extreme example close to the minimum focusing distance at 200mm f4.

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm f4 and close to minimum focusing distance.

If you’re into macro, the longer focal length of the Leica DG 50-200mm gives it a small advantage over the Olympus 40-150mm PRO in terms of maximum reproduction. In the example below I focused as close as possible to the subject with both lenses at their longest focal lengths and the Leica has delivered a slightly tighter field-of-view, although again nothing you couldn’t match with a minor crop on the Olympus.

Above: Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm (left) and Olympus 40-150mm PRO at 150mm (right), both at closest focusing distances

But how does the potential for blurring – not to mention the quality of the rendering – compare to the Olympus 40-150mm f2.8. Once again the Olympus boasts a brighter focal ratio at the long-end, but doesn’t zoom quite as far. To compare them I shot two subjects side-by-side with both lenses. First-up a portrait of your’s truly with both lenses set to an identical focal length of 150mm and their maximum respective apertures.

Above left: Leica DG 50-200mm at 150mm f3.9. Above right: Olympus 40-150mm at 150mm f2.8.

Above you can see the difference almost one stop of aperture makes at 150mm: f3.9 on the left and f2.8 on the right. Is it as much as you were expecting? The Olympus on the right at f2.8 definitely has greater and more attractive blurring than the Leica on the left at f3.9, but it’s not a huge difference. And remember the Leica has the possibility of a longer focal length at its disposal, so let’s now compare it at 200mm f4 versus the Olympus at 150mm f2.8.

Above left: Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm f4. Above right: Olympus 40-150mm at 150mm f2.8.

In the example above, the Olympus on the right remains the same as before at 150mm f2.8, but for the Leica now zoomed-into 200mm f4, the camera was pulled back to match the subject size on the frame. The longer focal length does however mean less of the background is now visible which may or may not be preferable. In terms of blurring and rendering, I’d say the Olympus still delivers a smoother-looking result, but again the difference is subtle.

Here’s another example to compare them, again starting with them both at 150mm and their maximum respective apertures of f3.9

Above left: Leica DG 50-200mm at 150mm f3.9. Above right: Olympus 40-150mm at 150mm f2.8.

In the example above where both lenses were set to 150mm, the Olympus again delivers slightly softer and creamier background elements. The rendering is more attractive to me, although like the portrait example earlier, the difference may not be as significant as you assumed between f2.8 and f3.9 (their maximum apertures at 150mm). As before though, I repeated the test but this time with the Leica zoomed-into its maximum focal length of 200mm.

Above left: Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm f4. Above right: Olympus 40-150mm at 150mm f2.8.

In the example above you can see how zooming the Leica DG to 200mm on the left has delivered a tighter crop of the background elements which may or may not be what you’re after. In terms of rendering you may have a preference between the results above, but I’d call it fairly even. So ultimately while the Olympus 40-150mm PRO will deliver a slightly shallower depth-of-field throughout most of their shared range with arguably more attractive rendering at times, the difference in this regard may not be as much as you’d think.

In terms of focusing, both lenses are very swift and capable of snapping onto and tracking action, depending of course on which body they’re mounted on. I tried both lenses on the Lumix GX9, GH5 and the Olympus OMD EM1 Mark II and have no complaints regarding autofocus, although as noted in my reviews of each body, Panasonic’s DFD technology feels most comfortable tracking fairly predictable action whereas the OMD EM1 Mark II’s embedded phase-detect system feels better-equipped to deal with more random movement such as birds in flight. Here’s some examples of both.

Above: Ben cycling towards me with the Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm f4 on a Lumix GX9 body. Panasonic’s DFD technology easily kept him in sharp focus as he approached.

Above: One of Brighton’s finest with the Leica DG 50-200mm at 200mm f4 on an Olympus OMD EM1 Mark II body. The OMD EM1 Mark II focused this lens very successfully for unpredictable subjects like birds in flight.

Moving on, the Leica DG 50-200mm f2.8-4 features optical stabilisation that supports Dual IS to further enhance the performance when mounted on compatible Lumix G bodies. I wanted to test the optical stabilisation in isolation though, so mounted it on an Olympus OMD EM1 Mark II body which allows you to disable the body stabilisation and use optical only if desired.

When mounted on the OMD EM1 II, I required a shutter speed of 1/400 to successfully handhold the lens at 200mm without any stabilisation; reducing to even 1/200 resulted in quite visible camera shake ruining the image. With the Power OIS optical stabilisation enabled though, I could achieve the same result down to 1/6, resulting in an impressive six stops of compensation.

Out of curiousity, I repeated the test with OIS disabled and the EM1 II’s body stabilisation enabled instead. This time I achieved a sharp result down to 1/13, resulting in a solid five stops of compensation, albeit not quite the performance I enjoyed with the lens’s optical stabilisation alone. For the record, I also tried the combination with both the lens and body stabilisation enabled, even though they’re not designed to work together; in this instance I again needed a shutter of 1/13 or faster for a crisp image. So a good result for the optical stabilisation on the Leica lens there.

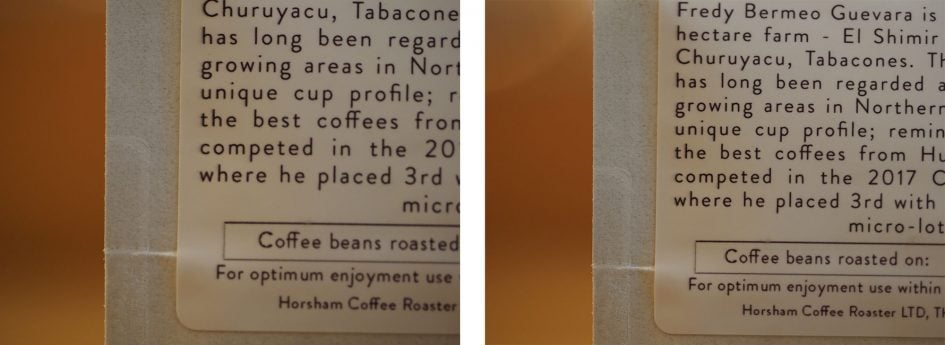

Above: Leica 50-200mm at 200mm and a shutter of 1/6. OIS disabled (left), enabled (right). 100% crops.

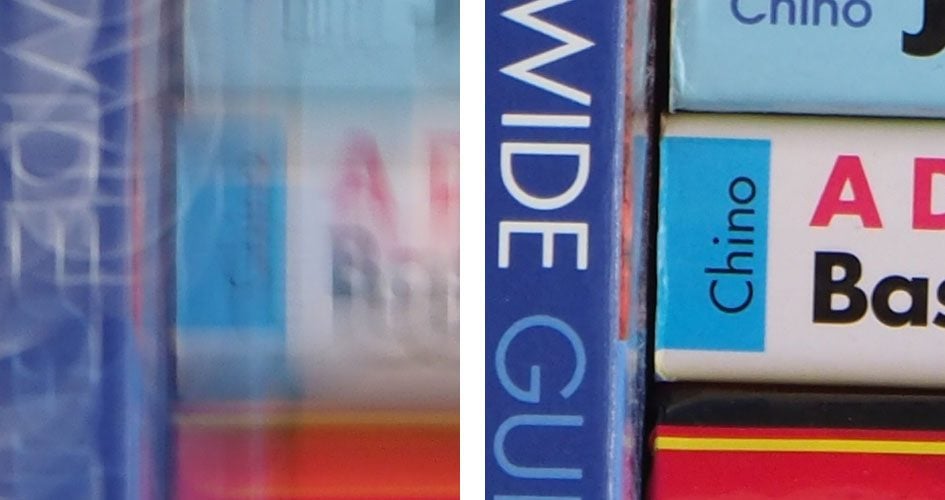

Now it’s time to compare their sharpness at long distances on my quality page or to check out more sample images. Alternatively head straight to my verdict!

Check prices on the Leica 50-200mm f2.8-4 at Amazon, B&H, Adorama, or Wex. Alternatively get yourself a copy of my In Camera book or treat me to a coffee! Thanks!

The Leica DG 50-200mm f2.8-4 is a compact and high quality telephoto zoom for Micro Four Thirds bodies upon which it delivers a 4x range equivalent to 100-400mm. This is an ideal range for sports, action, distant portraiture and some wildlife too. The focal ratio may not be constant, but is sufficiently bright to give it the edge in low light and shallow depth-of-field performance over cheaper telephoto zooms. The focusing is fast and quiet, the optical stabilisation achieved up to six stops in my tests, and like all of Panasonic and Leica's collaborations, the build quality is excellent with smooth mechanics and a weather-sealed body. The compact dimensions and light weight also mean you'll almost always have it with you in your bag, versus larger models which often get left at home. The smaller size, longer reach and presence of optical stabilisation are the key benefits over the Olympus 40-150mm f2.8 PRO, but it's more expensive and lacks the constant aperture, crispness at shorter focal lengths, and physical benefits of its rival, so think carefully about your needs. Ultimately though another worthy addition to the Micro Four Thirds catalogue and one I can recommend.

The Leica DG 50-200mm f2.8-4 is a compact and high quality telephoto zoom for Micro Four Thirds bodies upon which it delivers a 4x range equivalent to 100-400mm. This is an ideal range for sports, action, distant portraiture and some wildlife too. The focal ratio may not be constant, but is sufficiently bright to give it the edge in low light and shallow depth-of-field performance over cheaper telephoto zooms. The focusing is fast and quiet, the optical stabilisation achieved up to six stops in my tests, and like all of Panasonic and Leica's collaborations, the build quality is excellent with smooth mechanics and a weather-sealed body. The compact dimensions and light weight also mean you'll almost always have it with you in your bag, versus larger models which often get left at home. The smaller size, longer reach and presence of optical stabilisation are the key benefits over the Olympus 40-150mm f2.8 PRO, but it's more expensive and lacks the constant aperture, crispness at shorter focal lengths, and physical benefits of its rival, so think carefully about your needs. Ultimately though another worthy addition to the Micro Four Thirds catalogue and one I can recommend.