Olympus PEN E-P1

-

-

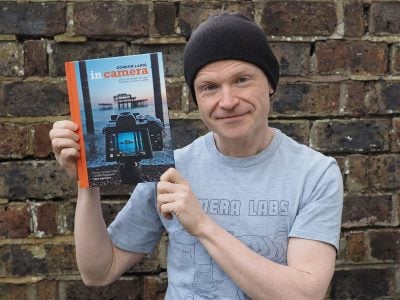

Written by Gordon Laing

Olympus E-P1 verdict

The Olympus E-P1 is the camera many enthusiasts have been waiting for. It packs a DSLR-sized sensor into a relatively compact body, with the added bonuses of interchangeable lenses and HD video. The advantage of using a DSLR-sized sensor is much lower noise, higher dynamic range and a potentially shallower depth-of-field than a typical compact can offer – and in use the E-P1 delivers all of these benefits.

Squeezing a big sensor into a small camera may sound like an easy thing to do, but involves over-coming a number of technical hurdles. Sigma was the first to achieve the physical goal with its DP1 compact, although this suffered from a number of operational caveats which ruled it out for many photographers.

The E-P1 achieves the same goal by adopting the Micro Four Thirds standard developed by Olympus and Panasonic. This takes the sensor size of the existing Four Thirds DSLR standard, but dispenses with the traditional SLR mirror and optical viewfinder to allow a much shorter lens to sensor distance. This in turn enables smaller and lighter cameras to be built, while the mount allows different lenses to be fitted – something the Sigma DP1 and DP2 can only dream of.

As we said at the start, the bigger sensor equips the E-P1 with all the noise, dynamic range and depth-of-field advantages of a DSLR – or at least a Four Thirds DSLR anyway – but it’s important to look beyond the hype of the sensor and consider the camera as a whole compared to both DSLRs and traditional compacts. As you might expect from a pioneering product using a fairly new standard, the E-P1 both delights and disappoints.

First the good news: the sensor performs similarly to the Olympus E-620 and E-30 bodies, and as such delivers much lower noise than a typical compact, although not quite in the same league as the best APS-C models like Nikon’s D5000 and D90. In our High ISO Noise results page you’ll see the E-P1 holds it together very well between 100 and 400 ISO and still looks good at 800 ISO. Between 1600 and 6400 ISO, the camera unsurprisingly suffers, but throughout the range it’s a big step-up from a typical compact. So while a good DSLR with an APS-C sensor will beat it, the fact it’s so much better than a traditional compact will be all some buyers need to know.

|

|

Bigger sensors and matching lenses with longer actual focal lengths also allow potentially shallower depths-of-fields than a compact, and again the E-P1 can blur a background on a portrait under the right conditions. Again not as dramatically as an APS-C DSLR with a similar lens, but still much better than a compact. We also found bright highlight areas which had become saturated on compact images retained detail on the E-P1 – again to a slightly lesser extent than a good APS-C DSLR, but still a respectable result. So in terms of image quality, the E-P1 delivers the goods as promised, or at least those from a Four Thirds DSLR – which is still a big leap from a typical compact.

The HD video on the whole looks pretty good with detailed results, albeit slightly over-sharpened like the still images. The Motion JPEG format allows easy editing, although the 2GB limit per file restricts you to around seven minutes of HD per clip. In terms of focusing, the E-P1 will bravely attempt to continuously autofocus if desired, but this isn’t sufficiently quick for general use, so you’ll be reverting to single or manual AF. Like most DSLRs with movie modes, it’s also easy to incur the wrath of the jello monster by wobbling the camera or attempting to zoom the lens while handheld.

Interestingly one of the criticisms often levelled at relatively new camera systems is a lack of lenses, but we’re not going to penalise the E-P1 in this regard. Micro Four Thirds is certainly youthful, but already has a number of compelling options, including two killer models from Panasonic: a 7-14mm ultra-wide zoom and a 20mm f1.7 pancake prime. Perhaps most exciting of all for enthusiasts though is the potential to create an adapter for almost any lens system you care to mention, including desirable Leica and Voigtlander options. Admittedly this is a benefit which applies to any camera which uses the Micro Four Thirds system, but it’s still a great plus-point for the E-P1, especially considering its built-in stabilisation.

Now for the things which didn’t work quite so well. In terms of size, the E-P1 may be much smaller than a typical DSLR, but it remains a relatively hefty compact which is more comfortable being carried over your shoulder or in a bag rather than squeezed into any kind of pocket. Olympus may have also shrunk the transportation size of the EP-1’s kit zoom, but it still adds a fair amount of bulk to the front of the body. There’s a very good reason the EP-1 (and to be fair, also the Panasonic GF1) often appear in marketing photos fitted with a thin pancake prime lens instead of their respective zooms – they simply look much smaller and in better proportion.

Sticking with the kit zoom, the mechanism which allows it to collapse can be slightly annoying in use. You’ll almost certainly have it folded back when carrying around, which means you’ll need to make a conscious effort to extend it before shooting is allowed. Annoyingly you’ll also need to have it extended to avoid the lens status warning when powering-up just to playback images.

|

General handling is an area where DSLRs normally excel over typical compacts, but the E-P1 is not as quick as you’d hope. The contrast-based focusing system is reliable, but fairly leisurely in operation, even with the firmware updated to version 1.1. Continuous shooting is faster than most compacts (delivering 2.5fps in our tests), but noticeably slower than most DSLRs at this price point. Certainly the E-P1 feels most comfortable shooting fairly static subjects like landscapes, buildings or posed portraits rather than the candid, action or reportage style of shooting its form factor looks built for.

Considering the price of the E-P1 and its target market of enthusiasts, it’s also disappointing to find a relatively low resolution screen. To be fair it is large with a fast refresh and wide viewing angle, but natural technological greed makes us inevitably yearn for a VGA screen, or at least one with 460k pixels. As it stands, a 230k screen is just a bit low-end for a camera of this class, and it certainly doesn’t help that Panasonic’s GF1 has a 460k model.

As the initial excitement over the big-sensor-in-a-small-package wears off, you’ll also notice a couple of key aspects missing from the E-P1. First is any kind of viewfinder, whether optical or electronic, eliminated to save space, weight and money. These are acceptable reasons, but Olympus’s solution is an optional optical viewfinder that’s only matched in coverage to the 17mm pancake lens – so it isn’t particularly useful at other focal lengths.

Secondly and more importantly is the absence of a built-in flash, a feature you’ll find on every compact including the Panasonic GF1 and Sigma DP1. Yes, the EP-1 has lower noise than most compacts at high ISOs, but that doesn’t mean you never need a flash. Sure, there’s a hotshoe for an external model, but we really missed an internal option for basic fill-in applications.

So before our final verdict, how does the E-P1 measure-up against its biggest rival, along with a typcial DSLR and enthusiast’s compact?

Compared to Panasonic Lumix DMC-GF1

The closest rival to the Olympus E-P1 is Panasonic’s Lumix GF1. Both are compact cameras based on the Micro Four Thirds standard and share much in common. They’re essentially the same size, they both sport 12 Megapixel sensors, similar continuous shooting, 3in screens with optional viewfinders, flash hotshoes, 720p HD video recording capabilities, HDMI ports, and as Micro Four Thirds cameras, they can also use the same lenses. At first glance then, you could be mistaken for thinking the choice boils down to preferences in styling and any difference in pricing, but look a little deeper and significant differences emerge.

In its favour, the Lumix GF1 has a screen with double the resolution (460k pixels vs 230k), it features a popup flash (unforgivably missing on the E-P1), faster auto-focusing, a more sophisticated auto mode, the choice of Motion JPEG or AVCHD for movie encoding, and it’s 39g lighter when both are fitted with their respective batteries. The GF1’s optional viewfinder is also electronic, as oppose to the E-P1’s optional model, which is optical and fixed at one focal length. Some may still prefer the E-P1’s optical solution, but many will prefer the GF1 viewfinder’s ability to deliver 100% coverage with any lens along with showing the same graphics as the screen; it’ll also tilt vertically.

Sounds like a slam-dunk for the Panasonic, but the Olympus E-P1 has some key advantages of its own, most notably built-in image stabilisation which works with any lens you attach. This is a major advantage for the E-P1 since the Panasonic relies on lenses with optical stabilisation, and already there’s several compelling options – including Panasonic’s own 7-14mm and 20mm pancake models – which aren’t optically stabilised. Pop them on the E-P1 though, and you’ll enjoy up to four stops of compensation. Not bad considering the camera is about the same size as the GF1 and only 39g heavier. The Olympus also has twin control dials, an electronic levelling gauge and includes the company’s Art Filters for in-camera special effects.

A lot will also boil down to which model you prefer the look of, with many enthusiasts falling for the retro styling of the E-P1 over the modern look of the GF1. And if you buy them in their respective zoom kits, the Olympus lens features a cunning design which allows it to fold down to just 44mm thick, compared to 60mm for the standard Panasonic 14-45mm in its shortest position.

It’s a tough choice, but for some it’ll simply be a case of weighing-up the built-in stabilisation of the E-P1 versus a more detailed screen, popup flash and faster AF of the GF1. But since we’ve waited so long for a decent compact with a big sensor, it’s great we now have the ‘problem’ of two compelling models to choose from. Check out our Panasonic Lumix GF1 review for more details.

Compared to Olympus E-620

It’s easy to get carried away with the E-P1 and forget that for the same money or less you could buy a DSLR with comparable quality, albeit in a larger form factor. Most obviously there’s the Olympus E-620, on which so much of the E-P1’s electronics are based. Both share (we believe) the same 12.3 Megapixel sensor, kit zooms with the same focal range, virtually identical image processing options including Art Filters and multiple aspect ratios and built-in image stabilisation which works with any lens you attach

In its favour the E-620 has a fully-articulated (albeit slightly smaller) screen, an optical viewfinder with a faster phase-change AF system, faster continuous shooting (3.4fps vs 2.5fps in our tests), a built-in flash, and a body which may be bigger, but one which some will find more comfortable to handle. The E-620 is also a little cheaper.

In its favour, the E-P1 is smaller and lighter, has a bigger (albeit fixed) screen, HD movies, a digital level gauge and an HDMI port. As you know, you’re paying the extra for the E-P1’s size, although the extra price in this case is also getting you HD movies and an HDMI port. The important thing is to think carefully about whether you really need the E-P1’s smaller dimensions though, as DSLRs of comparable quality with better handling to boot, are available at the same or lower prices – and at this price point, the Olympus E-620 is hard to beat. See our Olympus E-620 review for more details.

Compared to Canon PowerShot G11

When considering the E-P1, it’s also important to compare a traditional enthusiast’s compact, and this season the model to beat is Canon’s PowerShot G11. Both cameras feature flash hotshoes, RAW files and HDMI ports. Interestingly the E-P1’s body actually comes-up slightly smaller and lighter, but of course the crucial difference here is the G11 comes with a built-in lens. Fit the E-P1 with anything other than a fixed pancake prime and it becomes considerably larger.

So in its favour, the G11 packs a 5x optical zoom lens (with stabilisation, 1cm macro and a brighter focal ratio than the E-P1 kit zoom) into a body that’s only a little bigger than the E-P1 body alone. The screen is a tad smaller at 2.8in, but it’s more detailed with 460k dots and fully-articulated, allowing you to easily compose at any angle. It also has a built-in flash and an optical viewfinder. Crucially the G11 also comes-in around 40% cheaper.

In its favour, the E-P1 obviously has a much bigger sensor, and while Canon has sensibly reduced the resolution on the G11, it still can’t compete with the E-P1 at higher sensitivities. The E-P1 may be bigger and heavier when fitted with anything other than a pancake prime lens, but at least you can fit different optics where as the Canon is stuck with its 5x zoom, and all become stabilised thanks to the built-in sensor-shift system. Annoyingly the G11’s video remains standard definition, so HD movies is another advantage of the E-P1 over this model.

The decision between the two models of course boils down to whether you want or need the big sensor and interchangeable lens capabilities of the E-P1, and crucially if you’re willing to pay for them. If you’re happy with the sensor of the G11 and its optical range, then it offers a lot at a considerably lower price. It may not have HD video capabilities, but it’s still set to be a big seller. See our Canon PowerShot G11 review for more details.

Also consider

The E-P1 (and GF1) were beaten to the goal of squeezing a DSLR sensor into a compact body by Sigma and its original DP1, now joined by the newer DP2. We commend Sigma for kicking-off the process, but found the DP1 suffered from too many compromises to broadly recommend, although some will still accept its shortcomings for the Foveon sensor in a small package. See our Sigma DP1 review for details. And for those with bags of money, there’s always Leica’s X1 and M9.

Olympus E-P1 final verdict

When Olympus and Panasonic developed Micro Four Thirds, it was cameras like the E-P1 and GF1 which really had enthusiasts excited: the dream of squeezing a DSLR sensor and interchangeable lenses into as small a form factor as possible.

And in this respect, the E-P1 delivers the goods: the camera really does match (and in some cases slightly exceed) the image quality of models like Olympus’s own E-620 DSLR. Sure, like other Four Thirds models, Micro or otherwise, it may not match the noise levels of the best APS-C DSLRs at high sensitivities, but it’s a world apart from what you’ll achieve with a typical compact – and that in itself will be recommendation enough for many enthusiasts.

As described in detail above, there are some disappointments such as relatively slow focusing, a screen with average resolution and the absence of a built-in flash and viewfinder, not to mention a relatively high price for which you could buy a fairly decent DSLR which addressed all these concerns. But of course the thing which makes the E-P1 special is its size. It may be bigger than it looks, but it’s still much smaller than even the smallest DSLRs while delivering comparable quality – and that’s what you’re paying for.

For some it will be too expensive, or overly compromised in the aspects mentioned above. For others it’ll be exactly what they’ve been waiting for, and if you belong to the latter category, it essentially becomes a two-horse race between the E-P1 and its arch rival the Panasonic GF1. (Yes, we’re not including Sigma’s brave but ultimately disappointing DP1 and DP2 here).

As described above, both the E-P1 and GF1 have much in common including similar dimensions, but it really boils down comparing which style you prefer and weighing-up the built-in stabilisation of the Olympus against the more detailed screen, faster AF and built-in flash of the Panasonic. We can hear the gnashing of your teeth already – if only Olympus had fitted a flash and a better screen; if only Panasonic had built-in stabilisation. But at the same time it seems churlish to complain when after such a long wait we now have the ‘problem’ of not one but two compelling compacts with large sensors to choose from.

Ultimately the leisurely focusing, average screen resolution and absence of a built-in flash mark the E-P1 down from our top award – and indeed may sway you towards the GF1 – but it still easily comes Recommended, and depending on your outlook could represent your perfect camera. Micro Four Thirds is also becoming one of the most exciting systems in digital photography and we look forward to seeing how the standard develops – along with how rival manufacturers respond.

Note: for the scores below we’ve compared the E-P1 against budget DSLRs like the E-620, although obviously it could also be compared against compacts where it would score highly on image quality, but lower on value.

Bad points | Scores (relative to 2009 budget DSLRs) |

| ||

Build quality: Image quality: Handling: Specification: Value:

Overall: |

17 / 20 17 / 20 16 / 20 17 / 20 16 / 20

83% | |||