DJI Spark review

-

-

Written by Adam Juniper

In-depth

DJI Spark design

The Spark is a pleasure to hold. The battery clicks into the drone, forming part of the main body. As a result I felt a satisfying heft, despite the aircraft’s hardly-excessive weight, just 300g. In turning the 143mm-square quadcopter around to view it from all angles and there were no aspects that immediately felt anything beneath top quality. Some have argued that DJI should have gone for hinged legs, as they have with their Mavic Pro model, but I disagree; the solidity of the simple structure seems a much better choice here.

Above: The Spark sat atop a 15-inch MacBook Pro

The motors are firmly attached, and at the rear the Micro SD card and Micro-USB connector are discrete tucked away behind a hinged door bearing the Spark’s name (The Micro-USB can be used to charge the battery, taking about 90 minutes, or you can opt for the ‘Fly More’ pack which includes a charging hub). On the underside there are four rubber feet, and between the first two are two IR sensors and a camera which are used by the aircraft to determine its position and proximity to the ground, not for recording.

The only component of the main body that isn’t solid (apart from the propellers, obviously) is the two-axis gimbal. For those in the know, it is this component more than any of the others that impressed and surprised at the product launch. Sure DJI demonstrated a lot of clever selfie modes and gesture controls, which we’ll come to, but the inclusion of a motorized gimbal is unique in the ‘selfie drone’ category which, in truth, DJI are late to join. Yuneec’s Breeze and, arguably, the Parrot Bebop 2, are already contenders here, but both use digital image stabilization.

A powered, mechanical gimbal is simply better. It almost completely eliminates the very powerful camera shake the craft experiences as the drone dances around in the air. My worry was that it would feel flimsy. The Mavic Pro has a three-axis gimbal with tiny, exposed components and a fiddly travel protector and optional shield. The Spark’s, by comparison, is sprung and knock-resistant even while powered down, and not too exposed in the body to require additional shielding.

Above: DJI Spark sample image

Although it is a two-axis gimbal (‘roll’, which keeps the image level, and ‘pitch’, or up and down) and some drones boast three, the third, ‘yaw’ (left and right rotation) is the least significant. Yaw could soften a sharp turn, but that might risk an arm appearing in shot. At the higher end of the drone market, some gimbals offer independent yaw control, so the camera can point in a different direction to the drone. Here that’s not on offer, though for one user there is little benefit – it’s better to reposition the drone (or let its software do that for you).

All of this, by the way, is delivered in a solid polystyrene case which feels safe and easy to chuck into a day bag. As well as the Spark, there are spaces for two additional batteries.

Above: The Spark’s reliable (if simple) case, next to an iPhone 7 Plus.

DJI Spark features

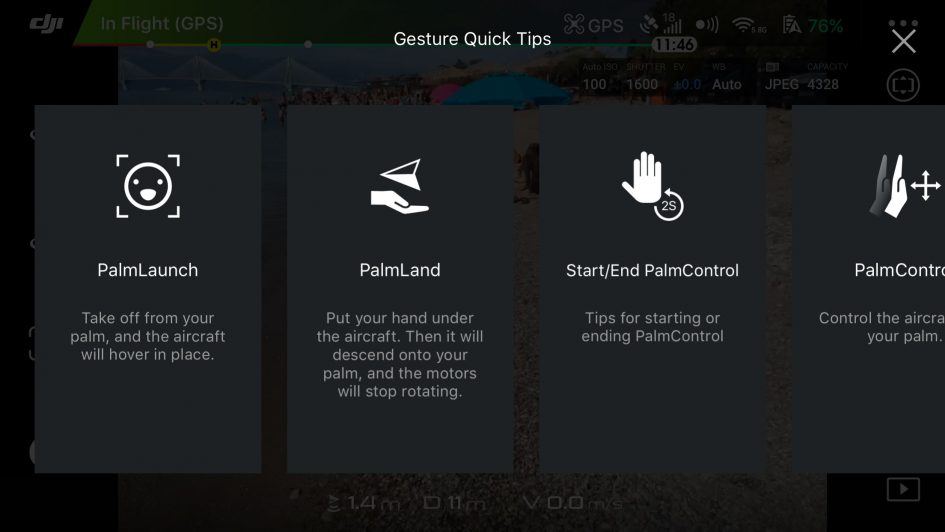

So, it’s well built. What about getting it into the air? Well that’s quite an interesting experience. Like everyone else holding a Spark for the first time, I wanted to launch it off my palm with the relaxed smile of a model in a media campaign. Yet, as an experienced drone pilot, I’m aware that propellers, even the plastic folding variety, can be pretty painful. So before I did, I made sure to install the DJI Go 4 app onto my phone and connect to the Spark’s Wi-Fi Zone (which it creates once powered up). Then I was left with a decision I don’t really recall seeing answered during the promo videos: once you’ve connected, set the drone to ‘gesture control’ mode (via the menu on the phone) and are ready to fly, where do you put the phone?

I found myself at a bit of a loss. My other hand didn’t feel natural and my pocket felt risky too – would I press the screen? I have a feeling that these are a set of worries that might not have crossed the mind of a first-time operator, especially as gesture mode doesn’t even need a phone connected, but it is undeniably weird depending on a device to follow your gestures. Especially one you know only has proximity sensors on the front and underneath.

Not only that, but if you’re used to an ‘ordinary’ radio controlled drone, then the palm-launch function’s requirement that you take off facing yourself – i.e. with the front of the drone facing you – is also somewhat troubling. The stick, or simulated stick, controls are most natural when the aircraft faces away from you, so one normally launches that way.

Undeterred, I extended my arm, Spark in palm, and reached to the back of the drone to double-tap the drone’s only button (in fact the button is on the battery, and a single tap serves to show a rough power-remaining on a 4-light scale when it’s powered down). The drone’s lights flashed to indicate that the camera had identified a face – mine – and the rotors began to turn. Moments later, the power kicked in and the Spark lifted off, with a noticeable but quickly corrected drift – only a few centimeters.

The next trick from the marketing? Palm control (the expression ‘feel like a Jedi’ crops up a lot in the online chatter). Stepping back slightly from the whirring, but definitely hovering, Spark, I raised my palm (all 5 fingers neatly together is a must). After a moment, the lights flashed green in recognition and I slowly moved my arm. The spark did indeed follow though, it has to be said, that there was a notable lag in the response, making me briefly doubt my Jedi credentials.

Interestingly the camera does not record video while you’re performing this nerdy-dance; though you can ask for the Spark to take a selfie for you by giving it the classic movie director’s framing-up finger square. Assuming it acknowledges the gesture at all, the aircraft will flash its lights, then it’s time to smile. Which, sorry, I don’t do well.

Fun though all this is, it’s not actually terribly useful – at this point the Spark is still hovering close enough for me to be able to get the same view with a selfie stick. What sets a drone apart is the ability to suddenly add a bit of context, and that, too, can be achieved with gestures. Theoretically. This was where I had a bit more trouble; what is meant to happen is that you wave your hand for two seconds at the Spark, which then ascends 3m, moves back 3m, and starts following you, but it does seem to have a bit of trouble detecting this gesture. There is a knack, and that’s to be quite robotic about it; keep your wrist still and wave just the palm. When it does get that extra distance, the 25mm EFL lens is suddenly in a much better position to put you in context, and the hand-box gesture still works just fine at the greater range.

All of the time the Spark isn’t responding to gestures it simply hovers in the air, holding its position using a combination of GPS and the downward-facing sensors. Although it won’t draw much comment from experienced drone operators, the accuracy is remarkable – even in a sea breeze it is able to hold position within a few centimeters in all axis. You are, however, burning through the battery’s 15 minutes of hover time (slightly less in wind), and eventually you’ll want to bring it home. Leave it too long and it’ll use those last minutes to return to the take off location and land of it’s own accord, but that’s not nearly impressive enough as the last gesture trick: PalmLand.

Standing like a giant ‘Y’ will help the Spark relocate you and it’ll return to arm’s length. To have the buzzing drone land on your hand, like a tamed bird, just stick out a very flat palm beneath the drone for a couple of seconds and it’ll land on it. Most times you try at least.

All that can be achieved without even taking your phone out of your pocket. Taking things a little more seriously, including recording video and using the more advanced photo features requires control, so the app can no longer be avoided. And here, as a seasoned drone operator, I also feel a little more at home. Relying on software features, however impressive, to position the aircraft feels a little risky to my mind, since the drone is only capable of detecting potential collisions ahead of it.

From a photographer’s – or videographer’s – perspective, this is also where the ability to pull off the best shots comes from; the point at which you take control of your drone and position it in relation to your subject. Personally I’m happiest not being the subject too, so that’s win-win.

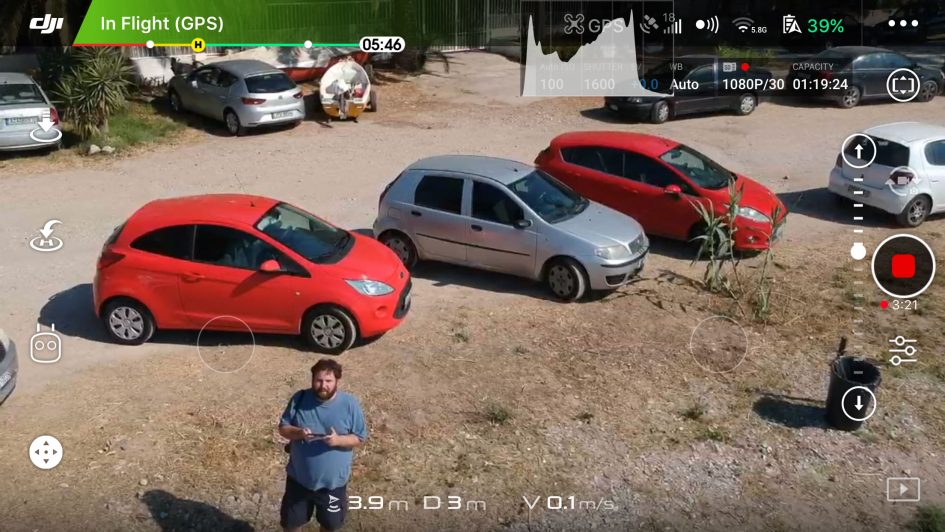

With the app connected, your device (iOS or Android) becomes a kind of FPV viewer and controller hybrid, with the Spark’s camera view overlaid onto the screen, and controls laid out around the edge. After dismissing an initial settings page, this is revealed properly. To some extent the display is self-explanatory, and in others it is not. It’ll certainly be familiar to seasoned DJI users.

At the top, is a status bar; a shaded area indicating whether a GPS lock has been achieved, the strength of the linking signal, and a slightly mysterious ellipsis at the right – this is for drone settings. The battery meter is a solid bar beneath this and the best in the business; not just a long gradually declining percentage meter across the screen, but a remaining-time estimator and the points at which the emergency return to home will kick in shown too. These adjust, so if you’re further away, more time will be allowed for return, though in the case of the Spark the effect is negligible unless you’re using the optional RC controller (also part of the “Fly More” package).

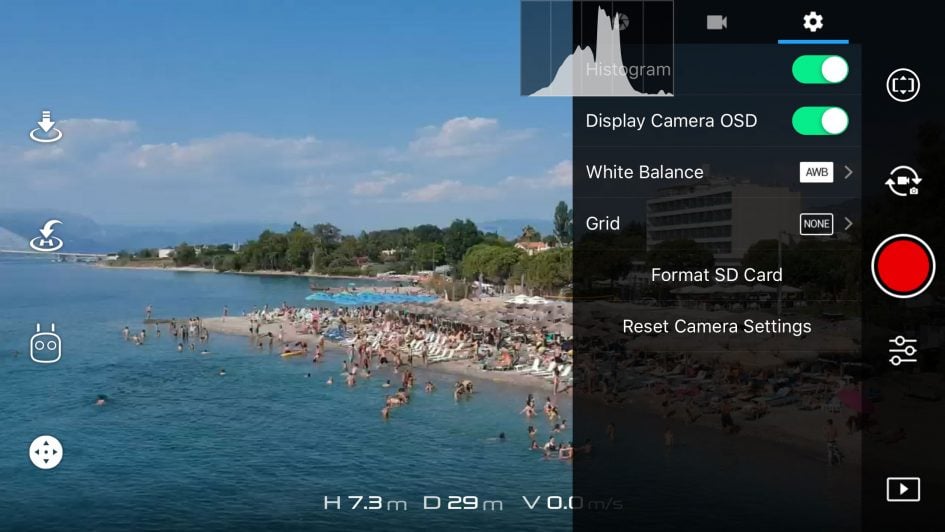

On the right you find the camera/video shutter button, flanked above and below by buttons for still or video mode and for camera settings, and on the left with a control for the gimbal’s vertical tilt. On physical controllers, including the optional RC, this is a control usually handled by a finger-wheel on the left shoulder of the remote, and on-screen is definitely a weaker solution, though still more natural to me, at least, than the tolerable option to use the phone’s gyro to ‘tilt’ the camera.

Above: DJI Spark sample image

On the left are the land button, the return-to-home button, and beneath that the flight mode button. Bottom left is a button to invoke the on-screen controls at any time – useful because some of the other flight modes remove the lightly-overlaid joystick controls from view.

In practice I found the flight mode button and the camera settings button, and the sub-menus they bring with them, to involve more than a bit of compromise on screen; one has to have faith in the Spark’s hover to devote concentration to the settings. Not a unique issue, and there were no problems, but it does make me ever-aware of the battery ticking down while I try to remember where functionality is tucked.

Above: On-screen camera settings in Manual. I found it easier to trust auto and occasionally tweak the EV.

In terms of video, the Spark offers 1080p at 30fps – no slow-mo at 720p which is a bit of a shame, but no great loss. The competing Yuneec Breeze has a 4K camera, but without a motorized gimbal the Spark is the clear winner in terms of output. Quality is a more than adequate 24 Mbps, and the colours are accurate (though the AWB can be over-ridden should you choose). Yawing fast (quick pans) will give the auto-exposure something to think about, assuming you’ve not gone manual, but it seems to keep up.

Above: Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only).

Above: Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only).

Above: Download the original file (Registered members of Vimeo only).

Simulated stick control allows you to orbit your subject for beautifully cinematic shots, so long as you’re able to stay in the 50m high / 100m long wi-fi range. I personally didn’t find this anything like as restrictive as I expected. I’m used to the 120m altitude and 500m range restrictions in UK law, in which transmission range is rarely an issue. Since Wi-Fi at home won’t even get to the next room, I was pleasantly surprised that, out in the open, it was possible to get the Spark as far as I’d want to go.

Above: Tracking a subject, the Spark can orbit it. But it’ll lose her if she walks behind that tree!

While precision was perhaps not as easy flying manually, DJI have seen fit to provide not only some beautiful ‘selfie’ style shots, which they call QuickShots, but their ActiveTrack mode too, in which the drone can orbit a subject you define by drawing around it on the screen. Assuming you’re not in a crowd (and aviation authorities wouldn’t approve of that), the Spark seemed readily able to do this, and then to orbit the subject.

Above: DJI Spark sample image

Still photographers also get a surprisingly generous set of options. That includes, auto exposure bracketing, multiple shot (burst), a ‘shallow focus’ feature a little like Apple’s iPhone 7 effect and a Pano(rama) mode that stitches images. You can also get an on-screen camera settings display, and even a histogram. Admittedly the latter, when enabled, is unhelpfully overlaid, presumably to avoid overcrowding, but photographic sticklers may still find it useful. After all there’s often a lot of light around making the screen hard to trust.

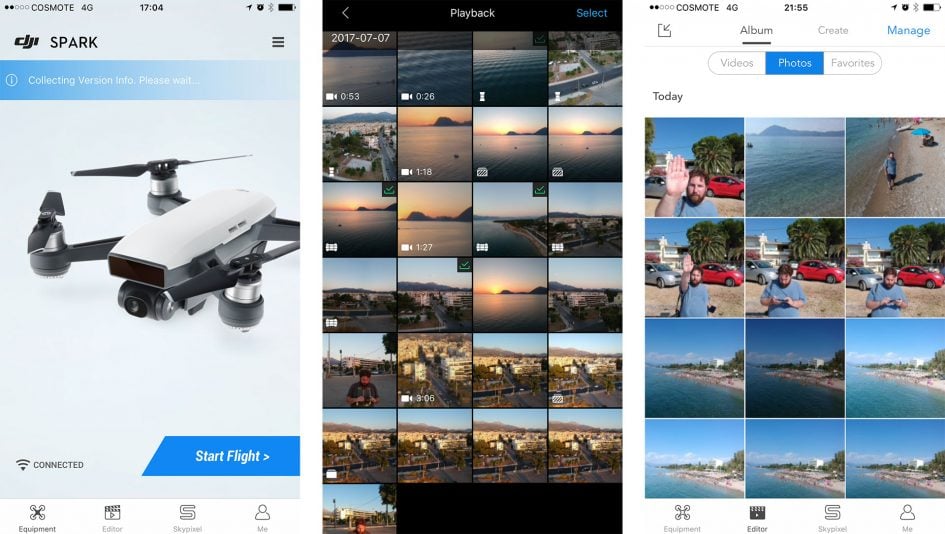

Shallow Focus and Pano mode images require you to download your images through the DJI app for post processing, and indeed all your pictures can travel this way. It is actually really well implemented though not natural if, as a photographer, you’re used to moving files to folders via a more physical means. If Apple Photos (or Android equivalent) is your go-to image storage location, this is almost seamless).

Above: A stitched panorama created from 9 images in the DJI Go app (3 x 3).

The trick is to wait until the end of the flight while you’ve only really got battery for an emergency landing, but still plenty to run the wi-fi, then switch the DJI app to its quite elegant ‘Editor’ interface. Here you’ll see thumbnails and previews of all that you have shot. You can choose to download each and will be notified if the image was ‘special’ in some way (e.g. a panorama); this will then be stitched on your phone. Given the lens is pretty wide already, the vertical panorama is probably the better of the options.

Above: The DJI Go app showing thumbnails and indicating which require further processing (pano, AEB etc.)

For social flowers, the app will also cheerfully create an edit of your days flying using a cache of the preview resolution video from the on-screen display (this is 720p). The effect is often very pleasing, and certainty quick to get out there, though if your followers are even less patient you can broadcast straight to Facebook Video.

Above: DJI Spark sample image