Canon PowerShot 350 retro review

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

Welcome back vintage camera lovers to another nostalgic tour of the early days of digital imaging, which today takes us back to 1997 when Canon launched the PowerShot 350 sporting one third of a Megapixel and a tilting screen. According to Canon’s official museum, this was their fourth PowerShot, albeit since two of those were PC Card models, it was arguably only their second digital compact with a conventional camera design.

Their first was the PowerShot 600 from 1996, a surprisingly large model which I’ve previously made a video about. One year later, the PowerShot 350 represented a considerable change in design, and in fact looking at subsequent models, it’s an outlier in the series. This is because Canon didn’t actually make the PowerShot 350. Instead it’s based on the Panasonic VZ-XP1 launched at the Comdex show one year earlier in 1996. This in turn became an OEM model for both Canon and I also believe Konica. See my video below for the full story, or keep scrolling for the written highlights with some sample images scattered throughout!

It wasn’t unusual during the early days of digital cameras for even the biggest names to share components or even rebrand entire models from other companies as they found their feet in the market. Preceding the later PowerShot A, G, S and Pro series, the 350 was a one-off, a gap-filler to test the market and one that’s quite hard to find today. I had a saved search on eBay for several years before one finally popped-up in what looked like good condition. It was sold as untested and after some haggling I bagged it for £32, or around $40. That’s roughly ten times less than its original launch price of about Y69,800. Let’s take it out 28 years later to see how it performs!

The PowerShot 350 departs from a traditional horizontal camera design to become a taller shape, almost square when viewed face-on. Fujifilm adopted a similar approach for their MX series launched in 1998, such as the MX-700. The 350 measures 90mm wide by 94mm tall, and 40mm thick at the thinnest point, bulging to 50mm on the grip. It’s pretty light at 290g without batteries, but fit the three AAs which power it, and it benefits from more heft. It’s fairly comfortable to hold with a mild grip on the front and a small indentation for your thumb on the rear, although the shiny plastic surface can feel a little slippery.

The front surface is home to a shiny shutter release with a click but no half-press, a slightly fiddly lever to open the battery compartment, the built-in flash and in the corner the lens, labelled as 6mm f2.8. In 35mm or full-frame terms, this is a fixed lens equivalent to about 43mm for a natural standard view.

The top panel is completely bare, so let’s move onto the left side where you’ll find a lever to set the lens between normal and macro focusing distances. The standard focusing range is 70cm to infinity, while sliding it to macro will allow it to focus as close as 3cm from the subject.

At first I assumed the lever would either set the camera to standard or macro mode, but it actually operates as a continuous manual focusing mechanism, smoothly adjusting the focusing distance from infinity down to 3cm. Slide it all the way down to maximum macro, and it’ll only deliver a sharp image from about 3cm away. So if your subject is, say, 5 or 20cm away, you’ll need to adjust the lever to a mid-point until the image looks sharp on-screen.

Behind a single flap are two ports: a digital output that’s used with the supplied serial cables for either PCs or Macs, and a 6v DC input for use with the AC adapter.

On the right side, behind the grip, is the battery compartment, with the PowerShot 350 powered by three AA batteries. Canon supplies a set of NiCads which are charged in-camera when the AC adapter is plugged in, although you can also power the camera from the mains adapter, or of course use disposable Alkalines instead. Canon proudly states these three power sources as a headline feature, although fast-forward to the present day and NiMH rechargeables represent a fourth.

On the underside you’ll find a second of those headline features, a slot with support for Type-I Compact Flash memory cards, considerably smaller and more convenient than the PC Cards employed by the original PowerShot 600. Canon supplies a 2MB card, good for 11 to 47 images depending on the quality setting, but also sells larger 4 and 15MB cards.

And finally, turning to the rear, a busy array of buttons and switches above and to the side of the 1.8in screen. Believe it or not, this is Canon’s first PowerShot with a built-in screen, and in the absence of an optical viewfinder, it’s exclusively used for composition, as well as playback. Note the small wheel to the right which adjusts the screen brightness.

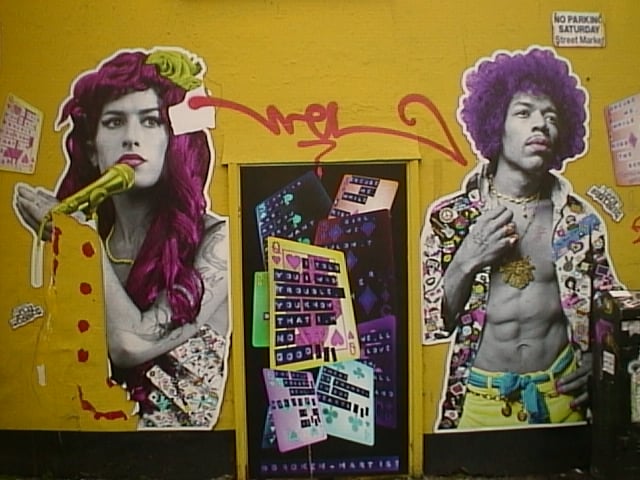

Impressively, the screen also angles out by around 40 degrees, allowing easier composition at low angles. Also note the fairly low frame rate and lagginess, although it is possible to frame-up if your subject’s not too fast.

As for the controls, there’s no fewer than ten buttons towards the top, including white balance, exposure compensation, flash and self-timer modes. The White Balance button toggles between Auto and custom. The NP Multi button allows you to switch the camera into a negative mode, which coupled with the close focusing capabilities allows you to capture and reverse frames of negative film, at least with an appropriate mount. Meanwhile the Multi mode displays four or 16 thumbnails in playback if you prefer.

To the right of the screen are three switches and a dial. The first powers the camera on and off with a short push. The second sets it between recording photos and playback. Next comes a fiddly dial to adjust the screen brightness, while below this is a three position switch setting the photo quality between Fine, Normal and Economy. Everything is operated by these buttons and switches alone with no screen-based menu system.

At the heart of the camera lies a one-third inch type CCD sensor sporting 350,000 pixels, or in other words, roughly one third of a Megapixel. This delivers images with a maximum resolution of 640×480 pixels, or as it’s known in PC terms, VGA. Canon quotes the sensitivity as being 120 ISO and the shutter range as one quarter to 2000th of a second, but exposures are completely automatic, with the only manual control being compensation to deliberately brighten or darken the image. Files are recorded as JPEGs only, again with three compression options. Given the same scene, the Economy, Normal and Fine modes generated files measuring 31, 70 and 145 KB respectively.

Fast forward 28 years and I had high hopes I’d be able to get the 350 working with minimal effort – after all, it used AA batteries for power and Compact Flash for memory, both of which are readily available today. But opening the battery compartment revealed why the camera was listed as untested: the terminals were green with corrosion, probably from a previous battery leak, and refused to make electrical contact.

Luckily all is not lost, as a variety of treatments can be used to clean the terminals, or at least remove enough corrosion for them to work again. I found a little WD-40 on a cotton wool bud – or Q-tip – could rub-off the worst of the corrosion, and while some was still remaining, the camera could at least now power-up with my eneloop rechargeables. Vinegar may be used to dissolve more of the corrosion if desired.

My 350 was sold with the original 2MB memory card, but since this was only good for 11 best quality images, I swapped it for a 32MB card from a later model, which worked fine. Oh and suffice it to say I did not bother with a serial cable connection to an age-appropriate PC running the required software. I just used a USB Compact Flash card reader on my MacBook. Easy. Note there’s no video clips as the camera didn’t have that capability.

Canon PowerShot 350 verdict

Canon’s PowerShot 350 arrived in the late Nineties into a melting pot of digital cameras. At this point no-one really knew how they should look or even if or when they’d represent a true alternative to film. In a rush to test demand, many manufacturers turned to other companies to get products onto shelves sooner than later with minimal commitment. Canon may have been an imaging giant, but the PowerShot 350 was based on a model made by Panasonic.

Either way, it was a substantial step-up over their first consumer compact, the PowerShot 600. Not only was it considerably smaller and better-looking, but it featured a screen, took standard AA batteries and recorded onto much more convenient Compact Flash cards.

But image quality was improving fast and the third-Megapixel sensor quickly became outdated, with models arriving soon after sporting a whole Megapixel or more. Just one year after the PowerShot 350, Canon’s third consumer model more than doubled the resolution but crucially presented a home-grown design that’s still recognisable today. This PowerShot A5 set a standard for Canon compacts going forward, based on the earlier film IXUS cameras and influencing the style of the future S series, not to mention the first digital IXUS models. These were true brand ambassadors.

As such the original PowerShot 350 and 600 have mostly become footnotes in Canon’s early digital camera history, filling a gap until there was greater demand. Today they’re both interesting models for collectors, and the 350’s close-focusing capabilities certainly set it apart from the crowd, although I did find it hard to nail the focus on the low-res screen. Plus the live view has quite a low frame rate.

If you’re looking for a more usable everyday vintage digital from Canon, I’d consider something from their PowerShot A, S or G series a few years later. But if you’re after something a bit more unusual, the 350 will certainly turn some heads and for collectors will represent a unique moment in Canon’s digital development.

Check prices at Amazon, B&H, Adorama, eBay or Wex. Alternatively get yourself a copy of my In Camera book, an official Cameralabs T-shirt or mug, or treat me to a coffee! Thanks!