Nikon D300s

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

Nikon D300s Movie Mode

More Nikon D300s features : Lens, AF, sensor and drive modes |

The D300s becomes Nikon’s third DSLR to feature video recording, with the implementation based on the earlier D5000 and D90 with a handful of useful enhancements.

As such, the D300s can record video at 320×216, 640×424 or 1280×720 pixels, all at 24fps and with sound recorded using either the built-in mono microphone, or in the first major enhancement, an external microphone connected to the new 3.5mm stereo jack – this makes the D300s the first Nikon DSLR to feature a microphone input.

|

Video is still compressed using the Motion JPEG system and stored in an AVI wrapper. The maximum file size is 2GB, although additional restrictions limit the HD mode to five minutes and the lower resolution modes to 20 minutes. The D300s will stop recording at whichever comes first: the time limit or file size. You’re looking at about 2.5MB per second for the HD mode with audio, using the D300s’s relatively high bit-rate of just under 40Mbit/s.

The D300s’s movie mode is an extension of Live View: with Live View running, you simply press the center of the multi-selector button to start filming and again to stop. If you’re using the lower resolution modes, the image will fill the same screen area as normal Live View, but if you’re shooting in 720p, there’ll be thin grey bars at the top and bottom of the image to indicate the wider 16:9 frame.

On the left is a sample movie shot in the D300s’s HD movie mode using the default settings; registered members of Vimeo can download the original clip here.

Some degree of exposure control is possible with the D300s movie mode. With Live View set to Tripod mode and the camera set to Manual or Aperture Priority, movies will be recorded using the aperture selected before entering Live View, down to a smallest value of f16.

So you can control the depth of field, so long as you remember to set the desired value before entering Live View. It’s also important to be in Tripod mode for Live View, as the Handheld mode is restricted to fully automatic exposure control. The shutter speed and ISO are always automatically selected by the camera. So you may not have the full manual control over aperture, shutter and ISO as found on the Canon EOS 5D Mark II, EOS 7D, or Panasonic’s Lumix GH1, but at least the most useful control over depth of field is available.

|  |

Autofocus is now possible with the camera set to Tripod mode in Live View, although like the Canon EOS 5D Mark II, this involves holding the AF-ON button down for several seconds as the contrast-based system locks onto its target.

Since this leisurely searching and focusing process will be recorded while filming, it’s no replacement for a camcorder (or the Lumix GH1) which effectively refocus in real-time.

|  |

Arguably the most important enhancement to the D300s’s movie mode is the presence of an external microphone input. The use of an external microphone, like the Rode stereo model, can transform the audio quality, and the D300s offers a page of sensitivity settings. It’s a very welcome upgrade as the sound from the built-in mono mic was disappointing in our tests.

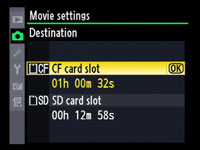

The final enhancement is the ability to edit movie clips in-camera. The D300s also lets you choose which memory card you’d like to record video too, although unlike stills, you can’t record footage to both cards simultaneously as backup, nor automatically swap to the second card one the first becomes full. Impressively, the HDMI output also remains active while filming, allowing videographers to monitor footage on an HD display – while filming, our PAL model output a 720p 60fps signal over HDMI.

|

VR is supported while filming to reduce camera-shake, but at the cost of higher power consumption, and you may also hear the system working in the background. The manual also warns of banding under artificial light and ‘distortion’ if the camera is panned horizontally or an object moves at high speed through the frame. It’s also possible to take a still photo while filming by simply pressing the shutter release button, although it will stop the video and won’t automatically restart afterwards.

Like the D90 and other video-equipped DSLRs, the results are a mixed bag: embrace the unique qualities a DSLR brings to video recording and you can enjoy spectacular results which would otherwise be difficult or impossible to achieve with a conventional camcorder. Fail to work within its limitations though, or simply become unlucky, and you can end up with very disappointing output.

|

Let’s start with the good news. DSLRs have large sensors compared to traditional camcorders, which allows them to perform better in low light, and also achieve a smaller depth of field. In practice this bears-out with the D300s. Its video really is much cleaner in low light than a typical consumer camcorder (see lens caveats below), and the potential depth of field much smaller.

You can easily throw the background out of focus, or switch focus from one subject to another – a technique we’re all familiar with from professional filming, but something that’s almost impossible to achieve on a consumer camcorder; see above for a grab from a movie sequence demonstrating the effect.

DSLRs also have the flexibility of interchangeable lenses, allowing you to film with exotic models including fisheyes and long telephotos, or those with macro or perspective control. Try doing that with your camcorder. The audio from the built-in microphone was however disappointing in our tests and both focusing and zoom adjustments could be heard as faint scraping in the background. If you want the best sound quality from the D300s, fit an external microphone sooner rather than later.

Now for the bad news. Hollywood and the pro movie industry may be used to manually focusing their lenses while filming, but most consumers aren’t. It takes some practice to get it right, and ideally requires a lens with a very smooth focusing ring and distance markings. It’s best-suited to rehearsed sequences with marked focus distances than spontaneous situations.

You’ll also notice zoom lenses for still cameras weren’t designed with video in mind: adjusting the focal length just isn’t as smooth, proportional or even quiet as a camcorder. It’s almost impossible to manually zoom the lens without twisting and shaking the camera, and DSLRs are simply the wrong shape to be held comfortably in front of your face while filming video for any length of time.

|

Speaking of lenses, it’s also important to compare like with like. If you buy the D300s with a typical general-purpose zoom, you may be surprised to find its video footage actually suffering from greater noise than your camcorder under low light. This is because the f3.5-5.6 aperture of most zooms is typically four to eight times slower than an average camcorder lens. So under the same light, a camcorder could be operating at a low sensitivity, while the D300s could be pushed to a considerably higher one. If both cameras were operating at the same sensitivity, then the D300s would deliver cleaner results, but with a typical zoom, the Nikon will almost certainly be working at a much higher sensitivity and effectively lose much of its advantage.

Like the D90 and D5000 before it, the D300s’s movie mode also suffers from motion artefacts often referred to as wobble, skew or jello. This is a well-known issue with CMOS sensors with rolling shutters which record each frame from top to bottom before returning to the top again for the next one. Should the camera or subject move during this process, the image can appear to tear, skew or wobble. Now many video cameras, both amateur and professional, employ CMOS sensors, but some suffer more from this effect than others.

Maybe we were lucky, but we suffered from fewer jello effects while filming with the D300s than the earlier models, but it’s still most definitely a risk waiting to trip-up footage shot under certain conditions. Handheld filming with wobbly pans and zooms is almost certain to result in undesirable artefacts. So like all DSLR movie modes, successful filming with the D300s involves learning what kind of motions best avoid the skewing effect and working around them.

Ultimately like other video-equipped DSLRs, the D300s will not replace your camcorder and if you try and use it in the same way for ‘normal’ shooting it will invariably disappoint or frustrate. Whether it’s the discomfort of holding the body, jerky zoom operation, necessity of manual focus, risk of skewing artefacts or the basic mono sound, it’s just not a viable video camera for all situations.

But the D300s can be a great complement to a camcorder, grabbing sequences with which would otherwise be compromised or even impossible. It has the potential to excel in low light and deliver an unusually small depth of field, and can also exploit unusual optics. In each of these respects it can thrash a conventional camcorder and approaches the capability of pro models costing a small fortune, but for the best effect you’ll need to learn its foibles and ditch the kit lens for something brighter with superior manual focus. Just understand its limitations, work around them and realise it will never replace a normal video camera or the way you’d use it.

It’s also important to know what the competition is up to. Canon’s EOS 50D may not have featured video, but the EOS 7D most certainly does. It offers both 720p and full 1080p video (in addition to VGA), along with the choice of frame rates and files which can reach 4GB in size. There’s also an external microphone input and full manual control over exposure. So with 1080p, adjustable frame rates, full manual control and potentially longer clips, the EOS 7D trumps the D300s in terms of video specifications, although until we test a final production 7D, we can’t comment on how well it works in practice. What we can say right now though is the Canon employs H.264 encoding, which is much harder to play and edit on a computer than the mild Motion JPEG format used by Nikon.

You can see more example footage filmed with the D300s’s movie mode in our Nikon D300s video tour. Now let’s check out how the D300s image quality compares in our results pages.