Panasonic Lumix GM1 review

-

-

Written by Gordon Laing

Intro

The Panasonic Lumix GM1 is a tiny system camera based on the mirrorless Micro Four Thirds format. Announced in October 2013, it packs the same sensor, image processing and much of the same features of the enthusiast-class Lumix GX7 into a considerably smaller body – indeed it’s the smallest Micro Four Thirds body to date and one of the smallest system cameras from any manufacturer.

Measuring 99x55x23.5mm, the Lumix GM1 has a main body that’s actually a little smaller than either the Sony RX100 II or even the Canon PowerShot S120, although there is a minor protrusion for the lens mount which makes it a bit thicker, and of course the Sony and Canon include built-in lenses in their vital stats. Mount a lens on the GM1 and it becomes thicker than either of these models, but the new 12-32mm f3.5-5.6 kit lens is sufficiently slim for the combination to still be mistaken as a high-end point-and-shoot rather than a fully-fledged system camera that’s compatible with a broad and established lens catalogue.

Despite its size, the GM1 includes a popup flash (GN4 at 100 ISO), built-in Wifi with smartphone remote control (but no room for NFC), a 3in touchscreen, timelapse and stop motion video modes, focus peaking and offers continuous shooting up to 4fps with AF or 5fps with focus fixed. Some of the space-saving is thanks to a new stepper-motor driven shutter mechanism, which is used to end exposures up to 1/500, after which a 100% electronic shutter takes over to speeds up to 1/16000; if you prefer you can use the electronic shutter regardless of the exposure for silent operation. Ultimately while the GM1 succeeds in being one of the smallest mirrorless cameras around, it now finds itself directly up against a selection of fixed-lens compacts for enthusiasts with compelling messages of their own. So if you’re after a compact camera with great performance, which will be best for you? Find out in my in-depth review where I’ll be closely comparing it to the Sony RX100 II and Canon PowerShot S120, not to mention other system cameras!

|

Panasonic Lumix GM1 design and controls

The Panasonic Lumix GM1 is not just the smallest Micro Four Thirds camera to date, but the smallest interchangeable lens camera from any system. Photos of the GM1 in isolation really don’t do it justice – in person it’s much smaller than it looks, with a body that’s roughly the size of a pack of cards, and depending on region available in silver, black, white or orange finishes.

When mirrorless system cameras were first introduced, compact size was one of their selling points, but over time many have grown larger to satisfy the expectations of DSLR owners. Now the GM1 shows us what’s possible when mirrorless engineers aim for the smallest possible package. If nothing else, Panasonic should be congratulated for achieving this size while delivering the quality and much of the feature-set of the high-end GX7.

Measuring 99x55x23.5mm, the Lumix GM1’s main body is actually a little smaller than the Pentax Q7 system camera, not to mention the Sony RX100 II or even the Canon PowerShot S120, and while it inevitably becomes thicker when fitted with a lens, Panasonic has created a surprisingly compact kit zoom to go with it that adds little to the overall size and weight. Remember the GM1 also has the largest sensor of the four models mentioned here.

|

It’s important to discuss working combinations, so here’s what you’re looking at when fitting the GM1 with the 12-32mm kit lens. The Lumix combination measures 99x55mm, 48mm thick and weighs 274g including battery and lens. The Sony RX100 II measures 102x58mm, 38mm thick and weighs 281g including battery. Meanwhile the Canon PowerShot S120 measures 100x59mm, 29mm thick and weighs 217g including battery. You can see the GM1 and 12-32mm kit zoom pictured alongside the Canon S120 above and the Sony RX100 II below; I’ve powered-up the S120 in the photo above, but its lens folds back inside the body when switched off.

|

So of the three cameras, the Lumix GM1 manages to scrape the smallest profile when viewed from the front, but when fitted with the kit lens is 1cm thicker than the RX100 II and almost 2cm thicker than the S120. In terms of weight, the GM1 with the 12-32mm is essentially the same as the RX100 II, although the S120 is noticeably lighter. Obviously there’s important differences concerning sensor size, lens range, aperture and the chance to fit other optics, all of which I’ll discuss throughout the review, but just looking at the size, weight, and photos here, it’s clear the GM1 with kit zoom is closest to the RX100 II. The extra 1cm in thickness definitely makes the GM1 combination less pocketable than the Sony, but you can still squeeze it into larger pockets with reasonable ease. If you’re after something much more pocketable though you’ll be drawn to the slimmer and lighter Canon S120 which is almost half the thickness of the GM1 fitted with the 12-32mm. If you intend to squeeze any of these cameras into smaller pockets, every millimeter counts, so compare their thicknesses carefully.

The GM1’s body has a magnesium alloy shell, so feels reassuringly solid in your hands, although it’s not weatherproofed. Like the RX100 II and S120 there’s no grip on the front and little more than a button to push your thumb against on the rear. Panasonic has however coated the GM1’s front with a textured surface that is far less slippy than the RX100 II and lends it a classier appearance too. I’d say this gives it an edge in secure holding over the Sony or Canon, but there’s no denying there’s little to hold onto on any of them. Panasonic offers an optional grip accessory which adds a cylinder to the front of the camera, but I didn’t get on with its look or feel. It does however make the camera easier to hold steady. Ultimately I found two-handed operation was necessary on all three cameras for the best results in their kit configurations. If you’re intending to regularly use the GM1 with other lenses, I’d recommend trying it (and the optional grip) in person first as it becomes much harder to hold steady with anything other than the kit zoom mounted.

|

Moving onto controls, ports and other physical features, the GM1 is fitted with a small flash that’s manually released with a small switch and pops up to roughly the same height as the RX100 II’s auto popup flash. The GM1’s flash has a guide number of 4 at 100 ISO, but it’s hard to compare against the Sony and Canon as they quote distances with Auto ISO; that said I’d say the GM1’s flash unit is roughly similar in size to the RX100 II and is equally suitable for short-range illumination.

Unlike the RX100 II there’s no hotshoe, so you can’t mount any external accessories. While an external flash would arguably be overkill on a body this size, the lack of hotshoe or accessory port eliminates the chance to fit, say, an electronic viewfinder or external microphone. I’m not sure how many RX100 II owners exploit these accessories, but it’s nice to have the option and I don’t think a hotshoe would have had a significant impact on the GM1’s size and style as its upper panel controls already protrude by a couple of millimeters.

So after a hotshoe-sized gap after the flash, you’ll find the GM1’s focus mode control; a dial which lets you switch between AFS, AFC and MF focusing modes and also sports a programmable Function button in the middle. It’s unusual to find a physical control dedicated to focusing on a compact camera, but it’s a welcome addition to the GM1.

To the right of this is the shutter release button surrounded by a collar to power the GM1 on and off. I found the collar a little fiddly and in fact it sprung off at one point during my tests and failed to sit back on again for long, although to be fair I was testing a review sample which had been used (and probably abused) many times.

Finally in the right corner is the mode dial which protrudes by about 2mm from the upper surface. The mode dial and shutter release are similarly-positioned on the RX100 II, but are indented and flush with the surface. This not only makes the mode dial on the Sony harder to turn accidentally, but easier to turn deliberately thanks to a thicker profile. I personally found the GM1’s mode dial could be a bit fiddly to turn at times and always required a pinch between my thumb and index finger, whereas the Sony dial could be turned more easily by thumb alone, yet never found itself set to an unwanted mode by accident.

Interestingly this experience extends to the rear control dial. Both the GM1 and RX100 II are fitted with thumb-operated control wheels on the back which can tilt to select different settings to adjust. But I personally found I could rarely turn the GM1’s wheel without accidentally applying too much pressure on one side and entering a setting I didn’t mean to change; I’d be turning the wheel to adjust the aperture for example, but then suddenly find myself adjusting the white balance instead. In contrast the tilting action was stiffer on the RX100 II and I could turn the wheel confidently with my thumb without ever accidentally pressing it down. Now these things are very personal and like all cameras you get used to their operation over time, but for me I found the RX100 II’s controls suffered from far fewer accidental operations.

It’s also worth noting the Sony RX100 II and Canon S120 sport an additional customizable control wheel around their lens barrels. These can offer different functions, whereas on the GM1, any lens rings are either for zooming or manual focusing, depending of course on the lens you’ve got mounted.

The GM1’s rear wheel can be tilted up, down, left or right to access exposure compensation, drive modes, focus areas or white balance respectively. Pressing the trash button during composition fires-up the on-screen Q. Menu which gives you alternative access to these along pretty much any other shooting setting, including Photo Style, flash mode, movie quality, photo resolution and aspect ratio, compression, focusing modes, metering, compensation, ISO and white balance.

The Q.Menu can also be operated entirely by touch if desired, and advantage it shares with the Canon S120 over the non-touchable RX100 II. I’ll discuss their screens in more detail in a separate section of the review later.

Moving on, the GM1 has a single flap on the right side which houses two ports: USB / AV output and HDMI. The GM1’s single flap is a lot easier to open and close than the fiddly twin flaps on the Sony RX100 II, but on the other hand behind one of the Sony flaps is a Multi Accessory port which supports things like an optional cable release, an accessory that’s not available for the GM1. There’s no microphone input on any of these cameras, but with its hotshoe and side port, the RX100 II can accommodate an optional microphone accessory.

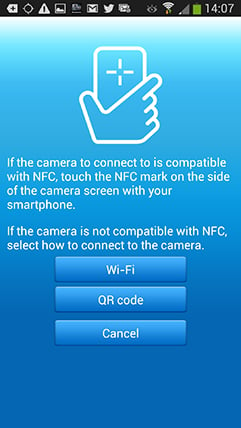

The GM1 is however equipped with Wifi, so you can remote control it using the very capable Lumix Image App for iOS or Android devices. Interestingly despite being a strong backer of NFC for touchless Wifi setup during 2013, Panasonic did not equip the GM1 with the capability – the excuse being there literally wasn’t room in the body for it. There’s also Wifi in the Canon S120 and Sony RX100 II, but of the three, the RX100 II is the only one that sports NFC too. Clearly there was a bit more room available in the Sony body.

Underneath in the combined battery / SD card compartment is a 680mAh Lithium Ion battery that’s good for 230 images under CIPA conditions. That’s roughly the same as Canon’s S120, but both fall below the 350 shots quoted by Sony for the RX100 II. That said, having used all three extensively, I’d say they can all run dry alarmingly quickly especially if you’re making use of Wifi or movies. For me the Sony still has the advantage though as of the three models it’s the only one which can recharge its battery in-camera over a USB connection. Some reviewers seem to hate this, preferring the ‘convenience’ of carrying a separate mains charger, but I frequently find myself with a low battery and no mains electricity nearby. In these situations though I invariably have a laptop or access to, say, a vehicle with a USB port, either of which could topup or even fully recharge the RX100 II. And even if you do have access to mains, isn’t it better to be able to share a single USB adapter than having to remember yet another proprietary adapter? I often found myself running low on power on the GM1, so without USB charging I’d strongly recommend carrying a spare battery.

Moving along, the GM1’s tripod thread is positioned in the middle of the lens axis where it should be, but with less than 15mm between the centre of the thread and the lens mount that’s flush with the bottom of the camera, it’s almost impossible to find a tripod plate which won’t prevent the use of anything but the slimmest lenses. Of my own collection of six Micro Four Thirds lenses, not one of them could be mounted on the GM1 when it was on my (small) tripod plate.

I understand Panasonic is developing more lenses specifically for the GM1 and I assume they’ll start narrow to accommodate a tripod plate before widening if necessary, but as it stands you’re unlikely to be fitting many lenses beyond the kit zoom when the GM1’s mounted on a tripod which sadly dampens one of its key selling points over rivals, especially as there’s no built-in stabilisation and little to hold the camera steady for handheld use.

Finally it’s worth noting Panasonic has fitted the GM1 with two proper strap mounts on either side of the body, presumably with the idea you may be mounting bigger lenses at some point. In comparison the Sony RX100 II and Canon S120 come with basic wrist straps that attach to one side only.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 lenses

|

The Lumix GM1 may look like a fixed-lens compact, but it is in fact a fully-fledged system camera with a Micro Four Thirds mount, which gives it access to the broadest native lens catalogue of any mirrorless system – and of course multiple third party lenses via adapters. This is one of the key advantages it has over fixed lens models like the Sony RX100 II and Canon S120.

It is however important to remember the GM1 is a very small camera with little to hold onto unless you buy the optional grip. As such it’s much harder to hold comfortably or steady for any length of time when using anything other than the kit zoom, and as noted earlier, you may also experience problems mounting it on a tripod when using other lenses due to their barrels extending below the camera’s base. Even fairly compact lenses in the Micro Four Thirds catalogue can look hefty on the GM1 – in the photo opposite you can see it fitted with the Olympus 17mm f1.8 lens, one of my favourite general-purpose primes, but one which again I couldn’t use on the GM1 when mounted on a tripod.

Panasonic designed the new 12-32mm kit zoom specifically for the GM1, and it’s truly a marvel of optical engineering. It’s incredibly light and measures just 24mm thick to match the diameter of the lens mount on the body so it’s hard to tell where one starts and the other ends; this also means the bottom of the lens is flush with the camera body and therefore avoids any issues with all but the largest tripod plates. The zoom ring is also positioned on the outer edge, again minimizing any tripod trouble.

The lens is a collapsing design that must be extended for use. There’s no lock, you simply give the zoom ring a firm twist and an inner barrel pops out, roughly by the same amount again; the zoom ring then starts at 12mm and rotates round to 32mm. There’s a normal lens cap you’ll need to remove (not the motorized type in the Sony RX100 II and Canon S120), but in return you get the chance to screw 37mm diameter filters right into it, for which you’ll need optional accessories on the other pair. Indeed I fitted my LEE Big Stopper ND filter on the 12-32mm for some long exposures you can see on my sample images page.

While it’ll take you a second or two to unclip the lens cap, you can at least twist the zoom ring very quickly and arrive at the longest focal length in about a second. In contrast, the Sony and Canon may automatically retract their lens coverings for you, but you’re looking at about four seconds between powering-up and zooming-in fully.

The 12-32mm is such a good match for the GM1 that it’s fair to believe many owners will rarely if ever remove it. Indeed in some regions, Panasonic is even marketing the GM1 kit as if it were a fixed lens compact, so it’s important to see how its capabilities compare to the competition.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 with 12-32mm coverage wide |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 with 12-32mm coverage tele | |

|  | |

| 12-32mm at 12mm (24mm equivalent) | 12-32mm at 32mm (64mm equivalent) | |

Above you can see the coverage of the 12-32mm kit zoom, which delivers a 24-64mm equivalent range thanks to the two-times field reduction factor of the Micro Four Thirds system. The 2.6x total range is only slightly less than the 3x ranges of typical 14-42mm or 18-55mm kit zooms, but satisfyingly starts at a wider 24mm equivalent compared to around 28mm as the norm.

But if the GM1 is competing against fixed lens compacts, it’s important to compare their lens specifications carefully. So to re-iterate, the GM1’s 12-32mm kit zoom offers a 2.6x / 24-64mm equivalent range with an f3.5-5.6 focal ratio. Sony’s RX100 II has a 3.6x / 28-100mm equivalent range with an f1.8-4.9 focal ratio. Canon’s S120 has a 5x / 24-120mm range with an f1.8-5.7 focal ratio. You can see the coverage of the RX100 II in practice below, from the same position as the earlier GM1 coverage shots.

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 II coverage wide |

Sony Cyber-shot RX100 II coverage tele | |

|  | |

| 10.4-37.1mm at 10.4mm (28mm equiv) | 10.4-37.1mm at 37.1mm (100mm equiv) | |

So the Sony starts out the least wide of the threesome, but zooms-in by around 50% more than the Lumix. Meanwhile the Canon shares the 24mm start of the GM1’s kit lens, but ends even longer than the Sony with almost double the reach of the 12-32mm. In terms of total range the Sony is longer and the Canon longer still, making them more flexible for general-purpose use, particularly for telephoto shots. Of course you could simply mount any number of telephoto lenses on the GM1, but here I’m comparing the most common kit configuration.

The focal ratio is also an important figure to take into account. When all three are set to their widest angle, the Canon and Sony are both two stops faster than the GM1 kit zoom, allowing them to use faster shutter speeds or lower ISOs under the same conditions – so when the RX100 II and S120 are at 100 ISO, the GM1 kit would need to use 400 ISO for the same shutter speed under the same conditions. Zoom them all to around 64mm (the longest end of the 12-32mm kit zoom) and the Canon and Sony remain at least one stop faster, so if they were at 100 ISO, the GM1 kit would need 200 ISO for the same shutter speed under the same conditions. So while the GM1 sports a bigger sensor, the slower kit lens erodes some of its advantage by forcing you to use higher ISOs than the Sony and Canon, and you can see the impact of this in my GM1 vs RX100 II noise results.

The focal ratio, focal length and sensor size also all have an impact on the potential depth of field, or how much you can blur the background (and foreground) on either side of a subject. To put this to the test I photographed two subjects with the GM1 kit and RX100 II, one close-up with the lens wide and a second portrait with the lens long – and in both cases with the aperture wide open. Here’s the portrait shot.

Sony RX100 II |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 with 12-32mm |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 with Olympus 45mm f1.8 | ||

|

|

| ||

10.4-37.1mm at 37.1mm f4.9 100mm f13.2 equivalent |

12-32mm at 32mm f5.6 64mm f11.2 equivalent |

45mm at f1.8 90mm f3.6 equivalent | ||

In the first two examples, above left and middle, you can see how the depth of field compares on the Sony RX100 II and Lumix GM1 when the latter is using its kit zoom, and when both are zoomed-into their longest focal lengths with their maximum apertures. As you can see, there’s not a great deal of background blur on either of them, which shouldn’t be surprising when you consider their full-frame equivalent apertures for depth of field at these focal lengths: f13.2 on the Sony and f11.2 on the Lumix with the kit zoom.

If you look closely at both samples you’ll see the size of the blur is actually roughly the same, but the RX100 II is arguably better for portraits due to the longer focal length being more flattering. That said, in this example, the RX100 II struggled to focus on the subject in lowish light whereas it proved no problem for the GM1. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere in the review, the ability to autofocus in much lower light is a key benefit of the GM1 over not just the RX100 II, but almost any camera. The other trump card for the GM1 is of course its ability to take a multitude of alternative lenses, so for the third sample, above right, I fitted it with the Olympus 45mm f1.8, which of course delivers a much shallower depth of field.

Sony RX100 II Depth of field for macro |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 with 12-32mm Depth of field for macro | |

|  | |

|

10.4-37.1mm at 10.4mm f1.8 28mm f3.6 equivalent |

12-32mm at 12mm f3.5 24mm f7 equivalent | |

In my second example, above, I set both cameras to their widest focal lengths, opened their apertures up to their maximum values and focused as close as possible to the catch on the jar of sugar. In this instance the Sony RX100 II, pictured above left, enjoys a clear advantage over the GM1 kit in two respects: first its full-frame equivalent aperture at the wide-end is much larger than the Lumix 12-32mm kit lens, and secondly it can focus closer to the subject too. Both allow it to deliver a much shallower depth of field than the Lumix 12-32mm kit lens if you’re willing to get close to the subject. Of course you could alternatively fit the GM1 with a dedicated macro lens, or simply one with a brighter aperture in order to deliver a better result, but the fact is with their default configurations, the RX100 II can capture a much shallower depth of field in a macro environment than the GM1 kit lens.

Like all Lumix G cameras apart from the GX7, the GM1 does not feature built-in sensor-shift stabilisation – instead you’ll need to fit optically stabilised lenses if you want to iron-out any wobbles. Luckily the 12-32mm kit zoom is stabilised, so to put it to the test I zoomed it into its longest focal length and took a series of photos with and without stabilisation enabled at progressively slower shutter speeds. On the day I found I could handhold the 12-32mm at 32mm (64mm equivalent) at 1/60 without stabilisation, but any slower and the wobbles emerged. Enabling stabilisation allowed me to handhold a sharp result at 1/15 (see below) and almost at 1/8, which means the system was delivering two to three stops of compensation. This isn’t as great as some of the systems I’ve tested, but a factor in successful handholding is without a doubt how easily you can hold the camera body steady to start with – and in this respect the GM1’s tiny dimensions don’t do it any favours. That said, the 12-32mm was good for two to three stops of compensation in my tests which is still very useful to have.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 with 12-32mm Optical Image Stabilisation off / on | ||

|  | |

100% crop, 12-32mm at 32mm, 1/15, 160 ISO, IS off |

100% crop, 12-32mm at 32mm, 1/15, 160 ISO, IS on | |

Before moving on, a quick note about the lenses available for the Lumix GM1 – it is after all a system camera with an interchangeable lens mount that’s compatible with the Micro Four Thirds standard. Micro Four Thirds, jointly developed by Panasonic and Olympus, is the most established of the mirror-less system camera formats, bringing bodies and native lenses to the market at least one year before its first rival arrived. Being first to market along with having not one but two major manufacturers behind it are two major advantages Micro Four Thirds enjoys over the competition, and it really shows when you compare their respective native lens catalogues. As of 2013, Micro Four Thirds had over 40 lenses available from Panasonic and Olympus along with third parties including Sigma, Tamron, Samyang, Voigtlander and others. So while many rival mirror-less formats are struggling to offer even one lens in every category, Micro Four Thirds typically has two or more options available. Whether it’s Fisheye, ultra wide, fast aperture, macro, super-zoom or good old general-purpose, the Micro Four Thirds catalogue has it covered, and many of them are great quality too – find out more in my Micro Four Thirds lens guide.

The ability to mount a wide variety of lenses on the GM1 is a big advantage it enjoys over rival compact cameras like the Sony RX100 II and Canon S120, but it’s not all roses. Since the 12-32mm kit zoom is just about the smallest lens in the catalogue, almost any other model will look and feel quite largewhen mounted on the tiny GM1 body. I tried it with my personal collection of six lenses and while it was great fun to shoot with fisheyes, bright primes and big zooms, all of them inevitably felt front-heavy and unbalanced on the GM1. Annoyingly most of the lens barrels also protrude below the base of the GM1’s body which makes it hard to mount them on a tripod. So while the GM1 can swap lenses, I wonder how many owners will exploit it on a regular basis; I suspect most will stick with the 12-32mm kit zoom, although it is at least nice to have the option to fit others if desired.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 screen

The Lumix GM1 is equipped with a 3in touchscreen as its sole means of composition. There’s no hotshoe, nor accessory port, so no means to mount an optional electronic viewfinder. In this respect it’s like the Canon S120, making the RX100 II’s hotshoe and optional EVF a unique advantage. That said, having a screen alone is not unusual for a compact camera and you can alternatively compose with your smartphone over Wifi using the Lumix Image app, see later.

The GM1’s panel itself looks to be the same 3in / 3:2 shaped / 1040k dot screen as the GX7 and G6, and like those models shares their lack of internal air gap, meaning the image is nice and crisp. If you’re shooting in the native 4:3 photo aspect ratio, there’ll be thin black bars running vertically down either side of the screen. Ironically the RX100 II has a 4:3 shaped screen but 3:2 shaped native images, which means there’s a thin black bar at the bottom where Sony positions shooting information. Only the Canon S120 has a screen the same shape as its native images, in this case 4:3.

|

As noted at the start, the GM1’s screen is touch-sensitive, like other Lumix G models, and also the Canon S120. For me this is a major advantage they have over the Sony RX100 II which does not have a touch-screen. I love being able to tap the part of the screen I’d like the camera to focus on, and also enjoy pulling focus between subjects in movies by tapping. But equally the Sony RX100 II enjoys a major screen advantage that’s lacking on the Lumix and Canon: the ability to tilt vertically upwards by almost 90 degrees and down by 45. This makes it so much easier to compose at unusual angles, but even under normal conditions I find myself frequently angling it up and shooting closer to waist height or on table-tops or tripods.

Touchscreen vs tilting screen? Only you can decide, but I use both in equal measure, so find myself wishing Panasonic and Sony had equipped their models with both technologies. I suspect a tilting screen would add too much to the thickness of the GM1 for Panasonic to consider for a future generation (besides, the GF has one), but a touchpanel would be easier to implement on a future RX100.

The GM1’s touch-screen interface remains a joy to use, and as explained earlier, you can adjust almost every setting with it, or if you prefer, ignore it altogether and use the physical buttons, dials and levers instead. Again I find it hard to shoot without a touch-screen now, almost always tapping on the area I want to focus on. I still enjoy tapping to refocus while filming video, and it’s also useful to drag guides around the screen to aid composition, not to mention swiping between images in playback and pinching to zoom.

Panasonic also lets you touch your way through the chunky menu lists and tap-out text using a mobile-style keypad interface on-screen – something the ZS30 / TZ40 super-zoom doesn’t allow. Suffice it to say you can also swipe between photos in playback, pinch to zoom, or tap an icon for a thumbnail view. In short there’s virtually nothing you can’t adjust on the GM1 using its screen, although again if you prefer you can ignore it altogether and operate the camera using its physical controls.

|

|

|

There’s also a broad array of display options when composing on the GM1. You can view a choice of alignment grids or draggable guidelines, a live histogram (also draggable), or a dual-axis leveling gauge. During playback there’s varying levels of exposure detail with each press, culminating in separate RGB and brightness histograms. In a missed opportunity though, Panasonic still resists the chance to auto-rotate images in playback as you turn the camera, so portrait shaped images in playback will never fill the screen.

|

|

|

Finally, a quick mention of the new Clear Retouch option in playback, which offers a clone-like tool to remove unwanted objects from images. In theory all you need to do is trace around the undesired object and the GM1 should remove it, but in my tests I just couldn’t get it to work satisfactorily, and even then the screen was too small and my finger too big to accurately select areas. So while it’s a nice idea in theory, it didn’t work well for me in practice. Others may have more mileage, but I prefer to do this sort of thing using Photoshop afterwards.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 autofocus

The Lumix GM1 has inherited the AF modes and capabilities of the GX7, which makes it pretty sophisticated for a compact camera, or indeed any camera. Most importantly, the GM1 offers 240fps AF drive for quicker response (on supported lenses), and usefully it can also autofocus down to -4EV compared to 0EV on the RX100 II.

The low light autofocusing capabilities is a specification that’s often overlooked in shorter reviews, but to me it’s one of the best things about the GM1. Like the GX7 and G6 before it, the GM1 will quite happily autofocus, even with a tiny AF area, under very dim conditions. I’m talking about shooting city scenes at night, people at parties, food shots in a restaurant or any interior when there’s very low light levels.

It’s easy to take it for granted until you compare it side-by-side against another camera. I shot with the GM1 alongside the Sony RX100 II, and once I was shooting in dim interiors, the Sony abandoned any attempt to focus on specific areas and simply tried to focus on anything at all in the frame; you know when it’s doing this as the single or multi AF areas are replaced by a huge green frame that indicates the camera is desperately searching for anything to lock-onto across pretty much the entire frame. Sometimes it’ll find something, but at other times it just hunts without success. Even when it does lock onto something, it’s invariably a light in the background rather than your desired subject. Meanwhile the GM1 just gets on with the job, focusing exactly where you want it to and nailing the shot. This makes it a far more capable camera in social situations, and what makes it all the more impressive in my tests was that the GM1’s lens was gathering four times less light at f3.5 compared to the Sony at f1.8 and still beating it.

Indeed the GM1’s low light AF is not only better than any other compact camera, but better even than most system cameras or DSLRs. The GM1, GX7 and G6 will simply focus more confidently in low light than almost any other camera on the market. It’s a major advantage for anyone shooting in low light.

The new 240fps drive means the GM1 is also very quick in better light, especially with lenses which support it like the new 12-32mm kit zoom. Fitted with the 12-32mm for most of my tests, the Lumix GM1 snapped onto the subject almost the instant I half-pressed the shutter release. Like earlier models, the touch-screen also makes it easy to tap on the subject you’d like to focus on, and I still very much appreciate the chance to adjust the size of the AF area using the rear wheel. I love dialing this down to a tiny square and just tapping the closest eye on portrait shots.

|

|

|

For even more precise focusing on the GM1, go for the pinpoint mode, introduced on the G3; this temporarily magnifies the image by three to six times for a really close conformation, while also letting you swipe the enlarged target area around with your finger until you settle on the desired part of the subject.

While the single AF performance of the GM1 is impressively quick and accurate in low light, it’s important to note it, like all Micro Four Thirds cameras to date from Panasonic, remains a 100% contrast-based system. Meanwhile Sony, Canon, Nikon, Fuji and even Olympus with its latest OMD EM1 have adopted hybrid AF systems for their latest models which complement contrast-based AF with phase-detect AF points on the sensor. Now in my tests these phase-detect AF points don’t necessarily make these cameras any faster at focusing, but they can make them more confident with less searching or hunting back and forth. This may not be a big issue for single AF acquisition, but can certainly help with continuous AF tracking for both stills and movies.

With its contrast-based AF system, the GM1 can’t help but hunt back and forth a little to confirm focus. Under ideal conditions, a phase detect or even hybrid system has the potential to nail it first time and just stop dead, which delivers a better hit-rate for stills of moving subjects and looks much less distracting for video too. Note I say under ideal conditions though, as plenty of hybrid AF systems I’ve tested do hunt from time to time, but generally speaking they do it less than a 100% contrast based system.

Is the absence of a hybrid AF system a big deal for the GM1? If you regularly use continuous AF for movies, then you may prefer a camera which has it, although I’d recommend you play my clips below as they prove it’s still pretty capable in this respect. As for continuous AF for stills, there’s not so much in it between the mirrorless systems – and again if a high hit-rate is critical to you for serious sports use, then you’ll be much happier with a semi-pro DSLR instead.

But when using Single AF for still photos, the Lumix GM1 performs admirably, nailing the focus very quickly and confidently even in very low light. Everyone has different priorities, but for me, this is where I want a camera to perform best of all and I suspect I’m not alone.

|

|

|

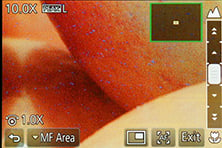

When the top dial is set to MF you can enable a wealth of manual focusing assistance. First there’s a magnified view, either using a small window in the middle showing an enlarged view at 3x to 6x, or a full-screen view at 3x to 10x.

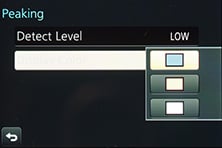

I’m also pleased to find the GM1 offering focus peaking. When this is enabled, the camera will highlight subjects that are in focus with the choice of three colours; the choice of colours varies depending on whether the peaking sensitivity is set to Low or High. Peaking is an invaluable aid when manual focusing for stills and video, and thankfully the GM1 (unlike many higher-end cameras) offers peaking for both including when you’re actually recording video. I used it to confirm the areas in focus during night photography, and also to know exactly when to stop pulling focus for video, and you can see an example of this below, where I manually focused the 12-32mm kit zoom using the on-screen controls described in a moment. Focus peaking is also a feature the GM1, GX7 and G6 enjoy over the flagship GH3 as Panasonic suggested to me that it was more complex than simply requiring a firmware update. Note the Olympus PEN EP5 and OMD EM1 now also offer focus peaking, but only for stills, not movies. For completeness I should add the Sony RX100 II also offers focus peaking, and like the GM1 it can be used for manual focusing while filming, using the ring control around the barrel.

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

A quick note on manual focusing with the 12-32mm kit lens, as you’ll notice it doesn’t have a manual focusing ring. Manual focusing is possible, but you’ll need to do it using on-screen controls. With the top dial set to MF, push the rear wheel to the left, reposition the magnified area if desired, then tap SET in the lower right corner of the screen to present a new touch-slider on the screen – this offers two focusing speeds in either direction, so you simply drag the slider with your finger to the desired speed icon and watch the lens adjust its focus. You can also do this while filming a video if desired. It’s not exactly the most convenient process, and one that’s best performed on a tripod, but that’s the sacrifice of such a small lens. At least it’s possible to manually focus this lens if necessary, and of course when you mount an alternative lens with a manual focusing ring, you simply twist it as normal to adjust the focus.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 shooting modes

The Panasonic Lumix GM1 offers a broad range of manual and automatic shooting options, selected using a small mode dial on the upper right surface. Along with the traditional PASM modes, there’s Intelligent Auto, Creative Filters (a choice of 22), SCN (a choice of 23 presets), Movie (with full manual control over exposure), and two Custom positions.

|

|

|

Starting with the scene presets, there’s 23 to choose from using the screen which cover the usual situations like portrait, sports, landscape and night compositions. Lumix watchers will note models like the GX7 offered 24 presets, with the missing one on the GM1 being arguably one of the most useful: panorama. Sadly the GM1 does not offer an auto panorama feature – there’s no official explanation why, although I suspect over-heating may be an issue as it’s the reason why the GM1 also lacks a Bulb mode and 1080 / 50p / 60p video. Whatever the technical reason, it’s shame not to have a panorama mode as it’s great fun to use on models which offer it, such as the Sony RX100 II; although in the spirit of fairness I should note the Canon S120 doesn’t offer panoramas either, although that’s more bloody-mindedness on Canon’s part than a technical limitattion. That said to be fair to Canon, the S120 does now sport three neat star presets for anyone wanting to attempt astrophotography.

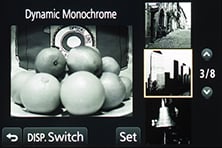

Moving on, how about one of 22 digital filters, including sepia, four monochrome options, high key, low key and the popular miniature mode. Here’s an example of six of them in practice.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 Dynamic Mono |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 Expressive | |

|

| |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 Impressive Art |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 Retro | |

|  | |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 Toy Effect |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 Sepia | |

|  | |

While cycling through these options, the camera previews the effect on a live thumbnail, and most effects can also be applied to movies by simply pressing the red record button. Here’s an example of the miniature mode applied to a movie, which simply inherits your existing quality settings – this makes it easy to record a Full HD miniature movie.

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

For complete control you can set the mode dial to Program, Aperture / Shutter Priority or Manual, unlocking a range of shutter speeds from 1/16000 to 60 seconds, with a fastest flash sync of 1/50. Camera enthusiasts will notice there’s two unusual figures there: a particularly quick fastest shutter speed and an unusually slow flash sync speed. The reason for both are the GM1’s shutter mechanism which is a little out of the ordinary.

One of the sacrifices made by Panasonic’s engineers in order to achieve a tiny body was to employ a stepper-motor controlled shutter mechanism – the compromise being that it’ll only operate at shutter speeds up to 1/500 and a flash sync of 1/50. While many compacts get away with maximum shutter speeds of, say, 1/2000, the top speed of 1/500 on the GM1 just isn’t fast enough in bright conditions or for action shots. So Panasonic opted to implement an electronic shutter which automatically takes over at speeds above 1/500 up to a maximum of 1/16,000. The electronic shutter operates silently, so if you prefer you can enable it for all exposures, including those below 1/500 if desired.

The reason you may not want to use an electronic shutter for all exposures though is they often suffer from rolling shutter artefacts, where if the subject moves during the sensor readout, it can appear skewed in the image. This can negatively impact shots of subjects in motion, such as following action from side to side.

I already knew the GM1’s electronic shutter was ideal for discreet environments, such as shooting hundreds of consecutive images for a timelapse (see movie section below), but wondered if it compromised photo quality at shutter speeds faster than 1/500. To find out I took a series of photos of kids jumping up and down at 1/500 with both the electronic and physical shutter, along with 1/1000, 1/2000, 1/4000, 1/8000 and 1/16,000 with the electronic shutter. I repeated the shutter selection with jetskis as they raced along the sides of Brighton Pier; here’s one I took at 1/16,000 and there’s two more on my sample images page.

| |||

I’m pleased to report out of hundreds of photos taken between 1/500 and 1/16,000, I only spotted image skew in a couple of them. It’s inevitably most obvious involving subjects you know, such as friends or family – indeed skew may have been present in other images, but went undetected as I wasn’t sure how they normally looked.

The bottom line is my tests made me confident to use the GM1’s electronic shutter at very high speeds whether to stop action, or simply use large apertures under bright conditions. It’s certainly nice to have access to a top shutter of 1/16,000 to really freeze the action as I have in the photo above. An electronic shutter is also invaluable for shooting silently. I would still advise being careful though, and avoid shooting subjects with the electronic shutter if they absolutely need to look undistorted, such as portraits – unless of course you could minimize the subject’s movement. Ultimately it’s another useful took to have at your disposal so long as you know when and how to best deploy it.

At the other end of the exposure range, the GM1’s longest shutter speed is 60 seconds. There’s no Bulb option, again another compromise of having a small body that could subsequently suffer from over-heating. To be fair, the Bulb mode on the GX7 only offered two minutes, so you’re not missing out on too much from Panasonic’s persepctive, but Olympus has been pushing this particular envelope with exposures as long as 30 minutes. But these are all just numbers. What happens when you dial-in the GM1’s longest exposure in practice? To find out I made a series of long exposures during dusk at Brighton Pier. The light conditions were too bright to allow a 60 second exposure, so I fitted a LEE Big Stopper Neutral Density filter which allowed me to expose for one minute at 125 ISO with the kit lens set to f6.3.

| |||

When viewing the image above at a reduced size it looks fine, but if you examine the original at 100% you’ll notice it’s sprinkled with quite a few hot pixels – and this is with noise reduction enabled too which takes a dark frame of the same exposure length immediately afterwards. I shot the same scene at 30 seconds and 15 seconds – both of which are available on my sample images page – and they were much cleaner with few if any hot pixels to deal with.

To put it in perspective, I was able to capture much cleaner images at 60 seconds with the Lumix GX7 and Olympus OMD EM1 and EM5, although those models begin to suffer at 2 minutes and beyond. This confirms the fears of Panasonic’s engineers: the GM1’s tiny body is too small to effectively dissipate heat from a very long exposure, hence the maximum 60 second limit and absence of anything longer. For the cleanest results though at 100%, I’d stick to exposures of 30 seconds or shorter on the GM1 unless of course you don’t mind cloning out a lot of hot pixels. In the GM1’s defense though, the fact you can easily mount an ND filter for long exposure work arguably makes it superior to rival compacts in this regard – just don’t expect the same performance as a larger system camera.

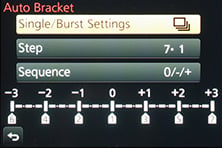

Moving on, like most Lumix G cameras, the GM1 offers very capable auto exposure bracketing with three, five or seven frames and a maximum spread of +/-3EV. Compare this to the pedestrian three frame bracketing on the Sony RX100 II and Canon S120 and it becomes clear the GM1 is the best choice if you’re into HDR work.

If I’m being greedy, it’s a shame there’s no way to trigger a burst of AEB frames using the self-timer – you have to trigger them one frame at a time which of course runs the risk of slightly nudging the camera between frames and causing alignment issues for HDR composites. The solution is to use a remote control, and this is where the camera’s built-in Wifi becomes particularly useful. While you can’t buy an optional cabled remote control for the GM1, you can alternatively use an iOS or Android device connected via Wifi to wirelessly trigger the shutter using the free Lumix Image app. I tried this and it works a treat.

|

|

|

If you prefer a more automatic approach to HDR, you can choose the HDR option from the recording menu, although note it’ll be greyed-out if you’re recording in RAW or RAW+JPEG modes. The HDR mode automatically captures three frames at one, two or three EV apart and assembles them for you, with the auto-alignment cropping the result slightly compared to a single frame. The camera only records one image though, so there’s no chance to access the three separate frames afterwards if preferred, and again no RAW option either. On the upside it will trigger the entire process with a single press of the shutter release, allowing you to capture an HDR using the self-timer. Here’s an example below with a single frame on the left and a composite three frame HDR at 3EV on the right. For this composition it’s not made a huge impact, although there’s definitely a boost in shadows and a better protection of highlights. Also notice how the auto alignment has slightly cropped the HDR result compared to the single frame version.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 Single frame |

Panasonic Lumix GM1 HDR mode at 3EV | |

|  | |

|  | |

0.4 secs, f4, 125 ISO |

1/4, f4, 125 ISO | |

The Lumix GM1 is also well-catered when it comes to time lapse sequences with the choice of two intervalometer modes and the chance to auto-assemble images into a movie afterwards. You won’t find anything like this on the Canon S120 or Sony RX100 II, nor indeed on many system cameras either.

|  |

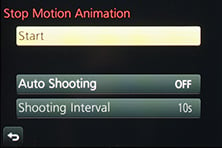

The Time Lapse Shot timer can be set to record up to 9999 frames at intervals from one second to a second shy of 100 minutes, and you can delay the starting time by up to 24 hours. The Stop Motion mode can also be set to record at regular intervals, or you can trigger the shutter by hand each time, allowing you to create animated movies.

It’s fantastic to have both of these modes at your disposal, and at the time of writing the Lumix GM1, GX7 and G6 were the only Lumix G cameras in the range to offer both modes. It’s also worth noting that the Olympus OMD EM5 does not offer any kind of built-in interval timer, and while the feature was introduced on the EP5 and refined on the EM1, it still only offers 99 or 999 exposures respectively. Bottom line, the GM1 and GX7 are better for in-camera interval shooting than most system cameras, and it’s a fun advantage the GM1 enjoys over rival compacts.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 Wifi

The Lumix GM1 becomes Panasonic’s latest camera to offer Wifi, although unlike the GX7, G6 and GF6 it does not include Near Field Communications, or NFC for short. Panasonic’s excuse is that there was simply no room in the body for it, although that does beg the question how cramped it is inside the GM1 considering NFC was included on models like the Lumix LF1. Either way, NFC only helps the initial negotiation on compatible handsets, after which the Wifi implementation is the same as models like the GX7 – and in a word, it’s good.

|

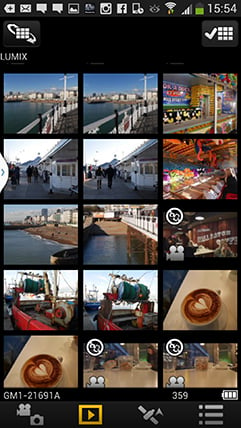

Wifi allows you to wirelessly browse the GM1’s images on the larger and more detailed screen of a smartphone, tablet or laptop, copy them onto these devices, upload them to online storage or social media services (either directly or via a smartphone), or become remote-controlled by a free app for iOS or Android devices. These are flexible and powerful features to have at your disposal, and more powerful than the Wifi implementations on the Sony RX100 II (which offers image sharing and basic remote control) and especially the Canon S120 (image sharing only).

In the absence of NFC, the first step to setting up the GM1’s Wifi is to press the function button atop the camera to either create a new connection, or load one you’ve previously configured. If you’re creating a new connection you can choose from ‘remote shooting and view’, ‘playback on TV’, ‘send images while recording’ or ‘send images stored in the camera’. For a smartphone / tablet connection, you should choose the first option for remote shooting and view. This then sets up the GM1 as a wireless access point, displaying the SSID name and password. You’ll then need to start the Lumix Image app, select Wifi as your means of connection, select the GM1’s network and enter the password.

Once your phone or tablet becomes connected to the GM1, you can remote control it, browse the images direct from the memory card, copy them onto the handset and if desired send them onto various storage or sharing services. You can also set the app to make a GPS log for subsequent syncing and tagging, which I’ll cover in a separate GPS section below.

|

|

|

The remote control feature is really neat, showing a live image on your phone or tablet’s screen and allowing you to take a photo or start or stop a video. You can tap anywhere on the live image to set the focus to that area or directly take the shot. If the camera’s mode dial is set to Aperture or Shutter Priority, you can remotely adjust the aperture or shutter speed respectively, and in Manual you can change both.

You can also adjust the drive mode, ISO, white balance, exposure compensation or focus area, and there’s also a Q.Menu button which presents a list of additional options you can remotely change including the flash mode, aspect ratio, resolution, compression, metering mode, photo style or movie quality. Again this is way beyond the control offered by many rivals.

Moving on, you can also use a connected phone or tablet to quickly browse the images in your camera on their bigger screens without having to copy them over first. This is more useful than it sounds. I found myself really enjoying scanning through a day’s shoot on my Galaxy S4 without having to remove the card, physically connect the camera or copy any unnecessary files.

|

|

|

To maintain a responsive experience which feels like the images are stored locally on your phone or tablet, the camera sends a lower resolution version. So you can pinch to zoom-in a little, but not as much as if you were viewing the original. But when you see an image you like, just press and hold it on-screen for a second and the Lumix Image app will let you save the original to your device or start uploading it to one of the social, sharing or storage services installed on your device. You can configure the app to provide shortcuts to two or three of your most used services which could include Dropbox and Instagram in addition to the more usual suspects. Or of course once the image is copied into your device, you could just exit the Panasonic app and handle it direct from whichever sharing or storage app you like via your phone’s gallery.

You can also choose whether to copy images in their original resolution, or in one of two smaller versions. It typically took about 20 seconds to copy a 5MB original JPEG from the camera to my Galaxy S4 from a distance of about 1m; it’s not possible to copy RAW files though. On some Wifi cameras we’ve noticed the JPEGs sent over Wifi can be modified (typically shrunk) even if ‘original’ is selected, but I checked the JPEG files wirelessly transferred from the GM1 against the genuine originals and they were identical, meaning you really can use the Wifi to make transfers or backups.

Alternatively if you’re browsing your images on the camera and you see one you’d like to share, just tap the camera against your NFC phone or tablet and it will automatically establish a temporary network and copy the original over; the entire process again takes about 20 seconds. This is a brilliant feature and makes it easy to share or store your images.

It’s so much fun interacting with the camera using a smartphone or tablet that it’s easy to forget the Lumix GM1 can also upload images directly to the internet by itself via a suitable Wifi connection. You can upload directly to Facebook, Twitter, Picasa, Youtube, Flickr, but there’s two gotchas. The first is the camera doesn’t have any kind of built-in browser to accept the terms and conditions of many public hotspots, so you’ll mostly be using home or office-based Wifi or a tethered connection with your smartphone. To be fair though, the only Wifi-equipped cameras I can think of which do have a browser to accept terms and conditions are Sony’s NEX 5R and NEX 6.

The second problem is before letting you upload anything directly from the camera you’ll first need to register for Panasonic’s free Lumix Club. Again this is an approach shared by most manufacturers, although unlike many, your images aren’t actually sent via this service. So if the images are going direct, why do you need to sign-up to Lumix Club at all? When it’s technically possible to upload direct from the camera without any third party apps or services, I’d prefer not to have to sign up for or agree to anything thankyou very much.

Once you do upload any images direct from the camera, they wait in a private Lumixclub album to be shared with a description. Since this requires you to have access to a computer, tablet or phone, it makes more sense to just use Wifi to copy the image from the camera to that device first and upload from there. The process is faster and avoids having to go through the Lumix Club.

|

|

|

As mentioned earlier, you can also configure the Lumix GM1 to automatically send images after they’re taken to a smartphone, tablet, or a computer, although as far as I understand it, you can only send images to a computer when both it and the camera are connected to the same access point, such as on a home or office network; I certainly couldn’t configure a direct peer-to-peer link between the Lumix GM1 and my MacBook Air, although direct connections are of course possible to smartphones and tablets as discussed earlier. Either way, it’s nice to have images automatically sent to devices which can subsequently upload them to cloud storage and backup if desired. Sure it’s heavy on bandwidth, not to mention battery power, but if neither are significant issues for you, it’s a compelling proposition. Or of course you could simply have a client viewing images on a tablet as you’re taking them, inside or out.

Like the Lumix GX7 and G6 before it, I was very fond of the Wifi capabilities of the Lumix GM1. I enjoyed browsing through a day’s shoot on the larger screen of a tablet and once connected it was a doddle to select original images to copy over for closer examination or sharing. The remote control facility was also fun and genuinely useful, although the range and response could vary significantly depending on surroundings and interference.

The only thing that could have been better was uploading direct from the camera to online services, but to be honest the more I test connected cameras, the more I think this is a red herring and that the actual getting online part is best left to your phone, tablet or computer. Beyond remote control or backup, the job of a Wifi camera should simply be to get your photos onto the sharing device as quickly and easily as possible, and in that respect the GM1 works very well – and again it’s another advantage it has over the more basic wireless implementations of most rival cameras, especially compacts.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 GPS

|

If there’s no room for an NFC chip in the GM1, there’s certainly no room for a GPS receiver, but like earlier models the Lumix Image app can be set up to record a GPS log with your phone that can later be synced with the camera later. There’s several steps to this process. First you’ll need to start the Lumix Image app then connect the camera to your phone using Wifi. Next you should select the satellite icon and then click the button for Time Sync which ensures your camera and phone agree on the current time. The third step is to tick the box labeled ‘Rec Loc Info’, after which the phone will record its current position at pre-determined intervals, the default being every five seconds.

Now you can merrily snap away with the GM1, safe in the knowledge that your phone should be recording your current position in preparation for a synchronization at a later point. The camera and phone don’t need to be in Wifi contact while you’re taking photos, only during the initial time sync and final data transfer. The only thing you need to remember is to take the phone with you and try to ensure it has a relatively clear view of the sky for successful GPS acquisition.

As with my Wifi tests earlier, I used my Samsung Galaxy S4 to try out the GPS syncing process. At first I kept the phone in the top of my backpack to maximize a clear view of the sky, but later became lazier and simply popped it in the pocket of my jeans. At first I was concerned the five second recording interval would hammer my phone’s battery life, but it didn’t seem to have a significant impact. Put it this way I could happily leave the logging running all day while also performing a number of camera, Wifi and internet tasks on a single charge.

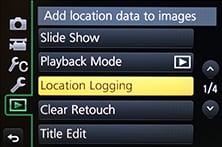

At some point you’ll need to transfer the location data recorded by your phone into the GM1, and this process again starts by connecting the camera to Lumix Image app running on the phone. Then from the satellite section, choose to ‘Send Location Data’, which normally takes a few seconds. This seems satisfyingly quick and simple, but the transfer is only one half of the process. The second is to have the camera actually apply the data to your images. To do this choose Location Logging from the GM1’s Playback menu, then select ‘Add Location Data’. You’ll then be presented with a list of date ranges for the periods where location data is available.

Actually applying this data to images can however be quite time-consuming. It can take a few minutes to append a day’s worth of shots, during which time the camera gives no indication of how far through the process you are; indeed the GM1’s screen powered-off on me a couple of times. But the process always completed successfully and my images were subsequently tagged with location details.

|

|

|

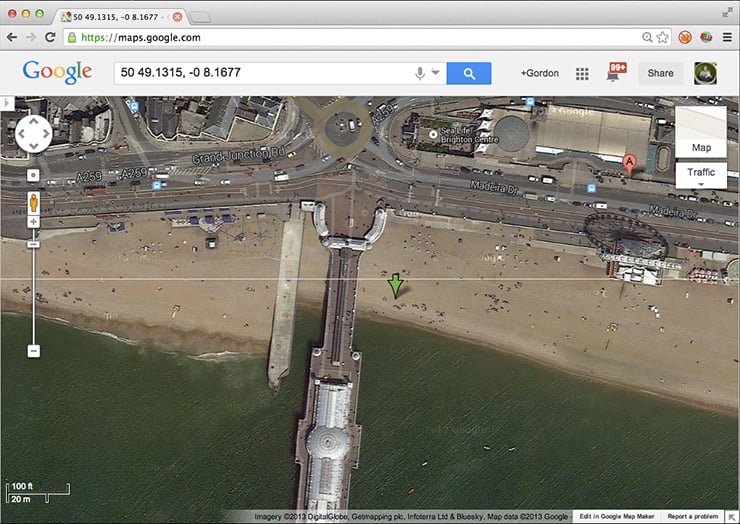

Out of curiousity I entered the co-ordinates of several images into Google maps and was impressed to find some were extremely accurate – indeed one I took was literally bang-on. Below is an image I took of Brighton Pier from the beach, and below that is the position recorded by the GPS on my phone and later embedded in the image file. I’d say this was within a couple of meters of my actual shooting position, and reassuringly my phone was in my pocket at the time, although I had remained fairly still for a few minutes prior to the photo.

|

|

However at other times with my phone in my pocket, the accuracy could reduce by at least 20m – sufficiently accurate for an approximate location, but not as precise as it could be.

And this is the big problem when you’re using a separate device to gather the location data. For the best results you have to make sure it’s got a clear view of the sky while you’re taking the photos, and since we’re talking about your phone, it’s more likely to be stuffed into a pocket or a bag. Obviously you also have to make sure you have it with you while you’re shooting. If only there was a device which was always with you and out in the open when you’re taking photos – oh wait-a-minute, there is, it’s called your camera.

Ultimately the process also isn’t that much different to making a log with a standard GPS device and syncing the data with your images once they’re on your computer using tagging software. The only benefits the GM1 has over this traditional process is being able to sync the GPS and camera using Wifi, transfer the data wirelessly and then tag the images within the camera itself, so there’s no computer or additional software involved. While this sounds more convenient, the process remains quite involved and I can’t help but wish Panasonic had found a way to build a GPS receiver directly into the Lumix GM1 as it had with its Lumix ZS30 / TZ40 super-zoom. It’s so much easier if the camera just handles it all itself and you only have to choose if the GPS is on or off. It would have also made this section of the review simpler: I’d have just written ‘if you enable the GPS option, it’ll record your position on images’. What’s not to like about that?

Panasonic Lumix GM1 movies

The Lumix GM1 inherits most of the recent GX7’s movie capabilities, with the most notable exception being the absence of a 1080 / 50p / 60p mode; I believe this was disabled on the GM1 due to concerns of overheating. But apart from that, the movie implementation appears to be the same as the GX7, which makes the GM1 a very powerful video camera.

As such, the GM1 may not offer 1080 at 50p or 60p, but it is available at 50i or 60i depending on region, and importantly it also offers the film-maker’s favourite 24p. It also offers full manual control over exposure with the choice of PASM modes, and like the GX7 there’s also focus-peaking for manual focus assistance while filming. The GM1 also inherits the GX7’s neat Time Lapse movie options, more of which in a moment. As you’d expect there’s no external microphone input, but then neither did the GX7. I should however note the Sony RX100 II allows you to connect an external mic accessory on its hotshoe.

|

|

|

|

|

Set the Lumix GM1 to AVCHD encoding and you can choose from 1080 at 60i or 30p for NTSC regions, or 50i pr 25p for PAL regions; the progressive options are encoded at 24Mbit/s, while the interlaced ones are at 17Mbit/s. Regardless of region you can alternatively choose a 1080 / 24p option at 24Mbit/s. There’s also a 720 mode at 60p or 50p depending on region and encoded at 17Mbit/s. Interestingly the 60i and 50i modes are encoded from a sensor output of 60p and 50p respectively, while the 30p and 25p modes start with 30p and 25p outputs, but are contained in 60i and 50i wrappers. None of this is ideal, but at least the 24p mode really is 24p and encoded at a nice high bit rate too.

Alternatively the Lumix GM1 can encode videos in the MP4 format for easier editing, with the choice of 1080 / 30p / 25p at 20Mbit/s, 720 / 30p / 25p at 10Mbit/s, or VGA 30p / 25p at 4Mbit/s. Again those frame rates are region dependent; unlike Canon and Nikon’s DSLRs, you don’t get both 60 and 50 or 30 and 25.

Audio is recorded using built-in stereo microphones on the upper surface and it’s possible to set the recording levels manually if desired, and if you like, also display mini peak level meters in the corner of the screen. Sadly there’s no chance to fit an external microphone though, unlike Sony’s RX100 II.

Like earlier models, the Lumix GM1 offers the choice of single or continuous AF modes, along with the option to pull-focus by simply tapping the subject on the touch-screen. Inherited from the GX7 is focus peaking, which surrounds subjects that are in focus with a coloured fringe. This makes it much easier to manually focus as you’ll know exactly when to stop adjusting the focus as third subject becomes highlighted. It’s a fantastic feature to have, and only the second Micro Four Thirds camera to offer it for video; annoyingly while the Olympus OMD EM1 now offers peaking for still photos, it’s not available while filming video. And lest we forget even Panasonic’s flaghsip video-oriented camera, the GH3 doesn’t have peaking at all. You can see examples of the various focusing options in my samples below.

As mentioned earlier, the Lumix GM1 offers full manual control over movie exposures, with PASM modes. You can adjust the aperture, shutter or sensitivity (the latter between 200 and 3200 ISO), and even make silent adjustments while filming, using on-screen sliders if preferred – this is pretty high-end stuff, considering the camera we’re talking about.

As before you can start and stop recording by pressing the dedicated red button on the rear. You can take photos while filming which share the same aspect ratio as the video, and with the choice of two quality options: if you don’t want the stills to interrupt the video, they can only be saved in a small size, but if you prefer a large version, it’ll temporarily blank the recording.

Also inherited from the GX7 are Time Lapse and Stop Motion modes, accessed through the main menus rather than the movie options. These can automatically assemble a movie from a sequence of still photos, either taken automatically by the camera at preset intervals, or manually as and when you’re ready. The auto mode is ideal for making time-lapse films, although the manual Stop Motion option allows you to create your own animated movies using drawings or models for example. Once you’ve finished capturing your photos, the camera can then encode them into an MP4 movie at your desired resolution and frame rate, although note it will inherit the original aspect ratio of the photos and won’t crop 4:3 to 16:9, so if you’re wanting a widescreen movie, don’t forget to set the photo aspect ratio to 16:9 first.

To put it to the test I set the camera up in a busy cafe, resting on a jar of sugar. Using the Time Lapse mode, I set it to capture an image every three seconds for 520 frames. I set the image shape to 16:9, as I wanted to create a 16:9 shaped movie later, and also reduced the image quality to avoid running out of space on the card. I also adjusted the exposure so the shutter speed was 1/8, in order to blur anyone in motion in the shot, as otherwsie sequeces like these can look a little jerky. I wanted to be fairly discreet, so switched the GM1’s shutter from mechanical to electronic, allowing it to shoot silently. Once the process was complete, the GM1 offered to generate a movie from the stills at a choice of frame rates – I opted for the best quality 25fps at 1080p and it took the camera about a minute to assemble it. Note you can generate a movie at a later point if desired from the playback menu.

I really enjoyed having the timelapse modes on the GM1 – and the GX7 and G6 before it – as they saved me from having to manually assemble a bunch of images myself later. Obviously doing it manually will allow you to crop and resize, not to mention supporting higher resolutions and frame rates, and you’re welcome to do this with the images you’ve captured in the timelapse sequence instead of – or even as well as – having the camera do it for you. Anyway, enough talk – let’s check out the cafe!

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

Just before sharing more movie samples, it’s worth making some comparisons with the GM1’s closest compact rivals. The RX100 II can film 1080p at 50p and 25p for PAL regions or 60p and 24p for NTSC regions, while the Canon S120 can film 1080p at 60p or 30p regardless of region, so both offer higher progressive frame rates than the GM1. Like the GM1, the RX100 II offers PASM exposure modes, but the S120 is fully automatic. Both the Sony and Canon offer motorized zooms built-in as standard, whereas the GM1’s kit zoom is manually operated. The RX100 II has a built-in hotshoe which can accommodate an external microphone accessory, whereas the S120, like the GM1 is limited to its built-in mics only. The S120 and GM1 both offer touchscreen focus pulling, whereas the RX100 II does not, but the RX100 II’s tilting screen can make composition easier at high or low angles. The GM1 and S120 allow you to apply the popular miniature effect to movies, but the RX100 II does not. All three offer focus peaking that remains active while filming, although unlike the GM1 and RX100 II, you can’t actually adjust the focus manually on the S120 once you start recording. Finally, the GM1 also offers a teleconverter option which takes a Full HD crop from the sensor, delivering a useful magnified view without any loss of video quality, and as a system camera, you can of course fit a wealth of alternative lenses for different effects. Right, now let’s get on with the samples!

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

|---|---|

| |

| |

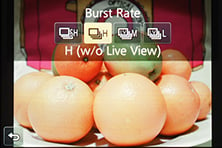

Panasonic Lumix GM1 continuous shooting

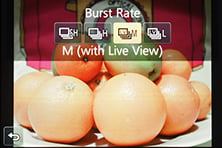

The Panasonic Lumix GM1 offers three continuous shooting modes with its mechanical shutter, quoted at the following speeds: Low at 2fps, Medium at 4fps and High at 5fps, or at 4fps with continuous autofocus enabled. Switch the camera to its electronic shutter and the High option accelerates to 10fps. There’s also a Super High option which uses the electronic shutter to deliver 40fps, albeit at a reduced resolution of 4 Megapixels. Remember the caveat about using an electroic shutter for subjects in motion though as they can appear to skew due to the way the sensor reads the data during an exposure.

|

|

|

The GM1’s speeds are essentially the same as the GX7 before it. Note the G6 also shares most of the same speeds, but its High mode squeezes out 7fps from the mechanical shutter, which is more useful for action than the 5fps on the GM1. There are however a number of additional caveats to be aware of though.

One of the problems with fast continuous shooting on mirrorless cameras is their ability – or lack of – to show a live image between frames, allowing you to follow subjects and keep them in the frame. The Lumix GM1 only offers Live View when shooting at the Low and Medium speeds. Set the camera to High and you’ll be looking at the last image captured between frames, which makes it hard to follow fast or unpredictable action as you’re effectively looking at what’s just happened, not what’s happening right now. As for the Super High mode, it blanks the display during the capture, but only for one second before the buffer’s filled.

To put the continuous shooting capabilities to the test, I fitted the Lumix GM1 with a freshly formatted SanDisk Extreme 16GB UHS Class 1 SD card, set the shutter speed to 1/500, the sensitivity to 400 ISO and fired-off a selection of bursts with different quality settings. Note for my tests I used the default processing settings.

I started with the High setting without Live View or continuous AF. With the quality set to Large Fine JPEG, I captured 100 frames in 19.82 seconds, corresponding to a speed of 5.05fps, almost exactly matching the quoted 5fps, and again the camera seemed quite happy to keep shooting at this speed while memory remained. I then set the GM1 to RAW, after which it captured 8 frames in 1.93 seconds, corresponding to a speed of 4fps, a little slower than the measured speed for JPEGs, and interestingly a couple of frames less in total than the GX7 managed to capture in my tests. As before the buffer flushed in just a couple of seconds.

I then switched to the electronic shutter, which at the High setting, boosts the speed to 10fps. This time for Large Fine JPEGs I managed to capture 14 frames in 1.76 seconds, corresponding to a speed of 7.92fps. Not quite the 10fps quoted, and also limited to bursts of 14 frames before slowing considerably and stuttering.

Finally, I tried the Super High mode, which again uses the electronic shutter. This blanked the screen for one second, during which time it captured 40 JPEGs, corresponding to a speed of 40fps, matching the quoted specification. Note the image size in this mode is reduced to Small, which is roughly 4 Megapixels. Again the GX7 out-performed it in this regard, capturing a burst of 80 frames over two seconds in my tests, which certainly suggests it enjoys a larger buffer.

So in practice the Lumix GM1 performed roughly as quoted, although this made it a tad slower than the earlier G6 which in my tests managed 6.4fps. That said, using its High speed, the G6 stalled after capturing 28 frames, slowing down significantly, whereas the GM1 kept shooting at its slightly slower rate. It’s down to the situation and photographer to decide if one approach is better than the other.

It’s interesting to compare these numbers to a DSLR like the Canon EOS SL1 / 100D, which in my tests delivered just over 4fps. This would suggest the Lumix GM1 and G6 are more capable at shooting action, but remember if you want either continuous AF or live view between frames on the Panasonics, they will slow down to roughly the same speed as the Canon, or a tad slower. And even in the modes with Live View, the tracking experience with an electronic viewfinder remains inferior to the instant feedback of an optical viewfinder on a DSLR. Indeed if you regularly shoot action where you need to follow the subject in the viewfinder, I still believe a DSLR is a better bet. But if the action is more predictable, like a stunt which takes place in a fixed spot, or where the subject is approaching or receding (and doesn’t require continuous AF), then the GM1 will have a good stab at capturing it.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 with Olympus 75mm f1.8. Continuous High with Electronic shutter | ||||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

1/16,000, f1.8, 400 ISO, Continuous High at 10fpss (approx 8fps in practice) | ||||

Here’s a sequence of 12 frames I captured with the GM1 and Olympus 75mm f1.8 lens using the High Speed mode and electronic shutter – as with my formal tests above, I found I could only capture bursts of 9-14 frames at the full speed (approx 8fps) in this mode before the rate slowed and stuttered. You can see this in the sequence above where the first nine frames are in quick succession, but the final three are spaced a little further apart as the camera slowed down.

The continuous shooting capabilities are certainly very usable, but it’s also important to compare them against its compact rivals. In my tests the Canon S120 could shoot Large Fine JPEGs at 15.62fps for an initial burst of five frames, then at 9.43fps until it ran out of memory. Meanwhile the RX100 II can shoot at 10fps, but only for a short burst of 13 frames. If you want to shoot longer bursts with the Sony you need to drop the speed to 2.5fps, which isn’t as useful as the 5fps unlimited mode on the GM1. So the GM1 and RX100 II actually share similar capabilities when shooting at 10fps, but the GM1 is quicker if you choose the reduced speed for unlimited frames. Meanwhile after years of producing cameras with terrible continuous shooting capabilities, Canon looks like its finally nailed it with the S120, which beats its rivals by delivering around 10fps for as long as memory remains. As Live View cameras though, none are great at tracking action as it goes past though – indeed you can see I struggled to keep the jetski in the middle of the frame in my GM1 burst above.

Panasonic Lumix GM1 sensor

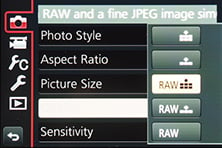

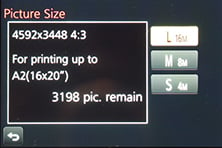

The Panasonic Lumix GM1 may look like a compact camera, but is a fully-fledged system camera based on the Micro Four Thirds standard, which means it has an active sensor area of 17.3x13mm, effectively reducing the field of view of all lenses by two times and delivering 16 Megapixel images with a 4:3 aspect ratio.

In this respect it’s identical to almost every other Micro Four Thirds camera on the market today from both Panasonic and Olympus. Yes the sensor is a little smaller than the APS-C sized ones in Sony’s NEX range and most non-pro DSLRs, but in my tests I’ve found little to no benefit of APS-C over Micro Four Thirds at all but the highest sensitivities; likewise for tonal dynamic range and highlight retrieval. And while pixel-peepers may get excited by a minor benefit in noise above 6400 ISO on the larger formats, it’s critical to consider the whole picture and the fact the slightly smaller sensor of Micro Four Thirds allows high quality lenses to be more easily designed. Indeed having now shot mostly with Micro Four Thirds for two years, I’ve found the access to a catalogue of excellent lenses has delivered better results overall than having slightly superior noise levels at very high ISOs.

So this means the tiny GM1 can essentially keep up with most system cameras and non-pro DSLRs at all but the very highest sensitivities. Impressive stuff, but for me the key is how it compares to other compacts aimed at enthusiasts. In the diagram below I’ve lined-up all the camera sensors in common use today and highlighted the Canon S120, Sony RX100 II and Lumix GM1 in red, green and blue respectively. The smallest sensor of the three by far is the 1/1.7in type in the Canon S120, which measures 7.4×5.6mm. You’d fit about three of those in the 1in type sensor used by the Sony RX100 II, which measures 13.2×8.8mm. Meanwhile, the Micro Four Thirds sensor in the GM1 is bigger still at 17.3x13mm.